After three years of war, Russia is still an energy superpower ?-Author Cam Fl.(rtr) PhD Sorin LEARSCHI

Article assumed by the Maritime Security Forum

Moscow’s descent from the top of the world’s energy producers is at the heart of the West’s strategy and Europe’s response to the energy confrontation launched by the Kremlin in 2021.

What differentiates energy powers from energy power centers? How will the three-year conflict in Ukraine affect Russia’s energy sector and its position among global energy producers? These two questions are fundamental for Romania’s and Europe’s energy future less than three years after the start of the war in Ukraine.

The sanctions and embargoes are designed to shake Moscow’s solid confidence and strike at the heart of its economic and political interests: energy. Knocking Moscow off the global energy production podium is the cornerstone of the West’s strategy and Europe’s response to the Kremlin’s energy confrontation.

The following analysis aims to examine whether Russia can still be seen as an energy power at the beginning of 2025.

Energy superpower or superpower

The scholarly literature to date on the role of superpowers in history and the influence and difference of superpowers compared to large and medium-sized powers has found wide circulation and success in popular discourse. Many authors have attempted to define superpowers based on the experience of the Cold War and the US-USSR conflict.

The dynamics of the bipolar conflict will continue in the future, given the great distance between these two entities and the rest of the international relations system. However, the collapse of the Soviet Union has brought a new wave of uncertainty into a configuration that was considered to be the most desirable and balanced for the international system.

In the last two decades, superpower studies have been revitalized by the rise of China as a global actor. Carsten Holbraad[i] vaguely points to strength, concreteness and potential as the main factors that define superpower status.

The few authors who have dared to use a clear scientific definition, “a superpower must be capable of executing a global strategy that includes the potential to destroy the world, have enormous economic control and influence, and offer a universal ideology”[ii]. Dukes’ definition is certainly accurate, but in a tense, yet highly globalized and interconnected world, it does not pay attention to the multidimensionality of the superpower concept itself.

A closer analysis shows that this definition does not include the important question of how a superpower can define and establish itself as a superpower outside the military and national security sphere.

Over the past two decades, questions about what a superpower is, how a superpower is defined, and whether a superpower really exists have emerged with increasing clarity[iii].

In the case of Russia as the object of analysis, its emergence as a superpower has been studied with particular emphasis since the late 2000s, and the consolidation of Vladimir Putin’s leadership has led to precisely this kind of academic research. Over time, namely as we approach the recent events in Ukraine, and regardless of whether energy issues are at the center of the analysis, a polarization of views has become evident in academic research.

On the one hand, there are those who see Russia effectively returning to world superpower status, often in cooperation or symbiosis with China, while others report that Moscow is retreating to the status of a capital of secondary importance in the international framework[iv].

According to Rosefjelde[v], over the past 25 years, the Kremlin has regained its status as a moral superpower. Massive military power, a subservient democracy and a low standard of living for the majority of the population have characterized this period. Although economic discouragement and backwardness held back the realization of the country’s superpower potential, mineral and hydrocarbon wealth and considerable intellectual capacity fulfilled the (potentially) grand ambitions of the Russian elite.

Energy and mineral resource elements have always been among the main economic and industrial activities characterizing the country’s identity. They have also been repeatedly identified as an integral part of Russia’s foreign policy priorities.

Political discourse and energy identity in Russia

Lenin’s famous slogan “Communism means the electrification of Soviet power and of the whole country”[vi] still adorns Moscow’s main electricity grid. As Banerjee observes, electrification or, more generally, the energization not only of the Soviet industrial and economic machinery, but also of society and urban space, has remained in people’s memory as a turning point in history, as “the main technology and instrument in the modernization of the country.”[vii] The electrification of the Soviet Union was a turning point in history, as “the main technology and instrument in the modernization of the country.”[viii

However, in the first years after Vladimir Putin’s appointment to the Kremlin, a real “energy ideology” was created, with Moscow still a member of the G8 and a candidate for the position of “guarantor of world energy security”, and GAZPROM became a geo-governmental company.

Due to rising commodity prices on the market, the new international balance between supply and demand strengthened the desire for centralized government control over the energy sector[viii].

This, combined with changes in the construction of national identity, reinforced the argument that Russia is an “energy superpower” with. at the center of this ideology the view that Russia’s energy resources offer an opportunity to reshape the international balance of power. Stimulating growth to revitalize the economy and underpin the new foundations of Russian (super)power is part of it.

The “near abroad” is, first and foremost, a chosen place where Moscow needs to assert and re-launch its identity as an energy superpower, recognizing the antagonism of a global scenario in which rival powers are in constant conflict [ix] and make it a matter of growth, pride, power and independence. In short, these resources are necessary for mutually beneficial relations with other countries.

However, this discourse highlights some vulnerabilities, notably the risk of Russia becoming the EU’s ‘raw materials source’ . Similarly, Brussels itself can be seen as moving away from Moscow’s oil and gas model in its imagined energy transition, raising important questions about economic and political interdependence itself.

Thus, the evolving discourse in and around the energy superpower shows the nature of the challenge to Russia and the definition of the tools to meet it. Today, almost three years after the beginning of the Ukrainian conflict, all this should lead to a critical analysis of how energy and identity interact and are, in fact, a joint product of the bidirectional relationship that links them.

In this area, the narrative of Russia as an energy superpower is closely linked to the physical, infrastructural and material development of hydrocarbons with which its national identity is intimately linked and is a core element.

In analyzing Russia as an energy superpower, it seems important to emphasize two aspects that have not yet been fully analyzed.

The first is the replacement of foreign machinery and equipment with domestic equivalents, which is an absolute priority for the Russian domestic energy industry. This initiative is strongly supported by the political class, but it predates the war scenario in Ukraine, and the urgency of its implementation has accelerated due to the exit of many Western companies from the country.

In addition to partnerships linked to traditional forms of energy, such as hydrocarbons, Russia, according to Putin, “is making a serious contribution to global food and energy security”. Not only that, Russia continues to be presented at home and abroad as a serious partner in the fight against climate change. Gas, nuclear and hydropower account for around 85% of Russia’s energy mix and have been repeatedly highlighted as making the Kremlin one of the “leading contributors to reducing greenhouse gas emissions”[x]. Thus, even decarbonization, presented in a form and content very different from the European model, is one of the discursive tools through which Russia presents itself as an energy superpower abroad, with the focus on the discourses and narratives developed by Russia. Primarily, the focus is on ‘neighboring countries’, with a particular emphasis on Central Asian countries, India and China.

Russia as an energy power in neighboring countries

In the post-Ukrainian invasion scenario, the entire post-Soviet space has become more important in redefining Russia’s national strategy and identity. Relations with neighboring countries that were under imperial and Soviet control and influence have been partly redefined and redesigned by using energy as an instrument of diplomacy and power politics.

Russian President Vladimir Putin recognizes that, despite the “challenges it faces”, Russia “remains an important participant in the global energy market” and that “geographic spheres of energy cooperation” such as the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) and the Commonwealth of Independent States (Figure 1, 2) are rapidly growing buyer’s markets.

Energy and identity are fully intertwined elements in a country’s self-image and regional policy choices. In the energy sector, the project to establish a common energy market between the EEU member states has been repeatedly publicized in recent years, with the idea of using gas and electricity prices up to ten times lower than in the EU. The role and value of this “growing” initiative of Russia, which is largely responsible for it. The potential to facilitate “free and transparent” electricity exchange between Member States and to promote decarbonization and efficiency of the energy system has been constantly discussed over the last decade. However, the deadline for the implementation of this energy integration project from January 1, 2025 has recently been postponed to 2027.

Fig. 1 – EEU and trading partners

Fig. 2 – Central Asian gas pipeline network

There are several reasons for this delay, which inevitably and directly affect Russia’s identity as an energy superpower.

First, the administrative costs and services associated with market integration have so far been too high, and each energy system, from Belarus to Kyrgyzstan, had significant particularities. Integration should have provided alternative supplies for the former Soviet countries, but events have prevented the realization of projects initiated by Russia.

The countries of the Eurasian Economic Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) began to discuss the possibility of building an energy corridor – a direct power line from Russia to Kyrgyzstan through Kazakhstan.

Another interesting project is the construction of a long (current permanent) line from Siberia to Kyrgyzstan through the territory of Kazakhstan. This will increase trade between the EAEU states.

Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Russia are planning to form the common electricity market of the Eurasian Economic Union by January 1, 2025 by January 1, 2025 due to the integration of national electricity markets. One of the conditions for such a process is maintaining a balance of economic interests of producers and consumers.

At the moment, each member of the EAEU independently forms its own energy balance based on household needs. With the transition to the single market, the systems will be able to work, complementing each other

One of the obvious problems is the supply of gas from producing countries (Russia and Kazakhstan) to consuming countries (Belarus, Armenia and Kyrgyzstan). Indeed, existing bilateral agreements link the countries for decades to come.

However, in the context of strained relations, the case of Armenia, which is expected to be supplied by Gazprom by 2043, is particularly noteworthy[xi]. Moreover, the situation is worsening in terms of regional energy security. Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan (the latter not directly included in the EEU) have gone through several phases since 2021 in which energy and electricity supply is not guaranteed.

Indeed, energy security is jeopardized by massive power outages, especially in the cold winter months. Fragmentation after the collapse of the Soviet Union, rising nationalism and ethnic conflicts have affected the ability of Central Asian countries to compensate for energy shortages due to the interdependencies and infrastructure links that already exist in the region. Against this backdrop, Moscow has seized the opportunity to once again propose itself as a key partner in ensuring regional energy security.

In November 2022, President Putin himself proposed the so-called “triple gas alliance” between Russia, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan[xii]. This energy axis should solve the energy and electricity supply problems, as the Kremlin intends, given the role of gas in electricity generation.

This idea not only implies a largely unbalanced economic integration in terms of the value of energy in regional economic exchanges, but also shows that Russia is trying to persuade observer states such as Uzbekistan to join the EEU by exploiting the energy situation in the region. Indeed, thanks to the first two-year contract signed between Moscow and Tashkent in June 2023, Gazprom started supplying gas to Uzbekistan in September of the same year.

Thanks to pipelines built decades ago to transport gas from Central Asia to the Russian market, the flow of methane is now being piped through Kazakhstan. Subsequently, a 15-year contract between Gazprom and Kazakhstan’s QazaqGaz and another 15-year contract between Gazprom and Gazprom Kyrgyzstan allow Russia to supply gas to both Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan at a real economic value, albeit lower than the price paid by European buyers[xiii]. Thanks to the new partnership with Astana, Moscow has been able to use the complex pipeline network in Central Asia and has created new opportunities to reach the Chinese market further east through new routes[xiv]. These are all important steps that prove the strategy of diversifying energy exports from the European market to new buyers and clearly contribute to the Kremlin’s reconstruction of its energy identity as a great power. (Fig. 3)

Fig. 3 – Main Asian routes

Russia as an energy superpower in Asia

In an international scenario in which Moscow opposes Western embargoes and sanctions on its energy exports, it is fatal for Russia to seek new markets for its raw material exports or, alternatively, to strengthen existing partnerships.

The structural need to redirect Russian exports to the South and East was expressed by the President himself in the first weeks of the conflict. In the work of the Committee on Strategic Development of the Fuel and Energy Complex of the Russian Federation and the Committee on Environmental Safety, these geographic vectors were identified as priorities for both planning and building new energy infrastructure.

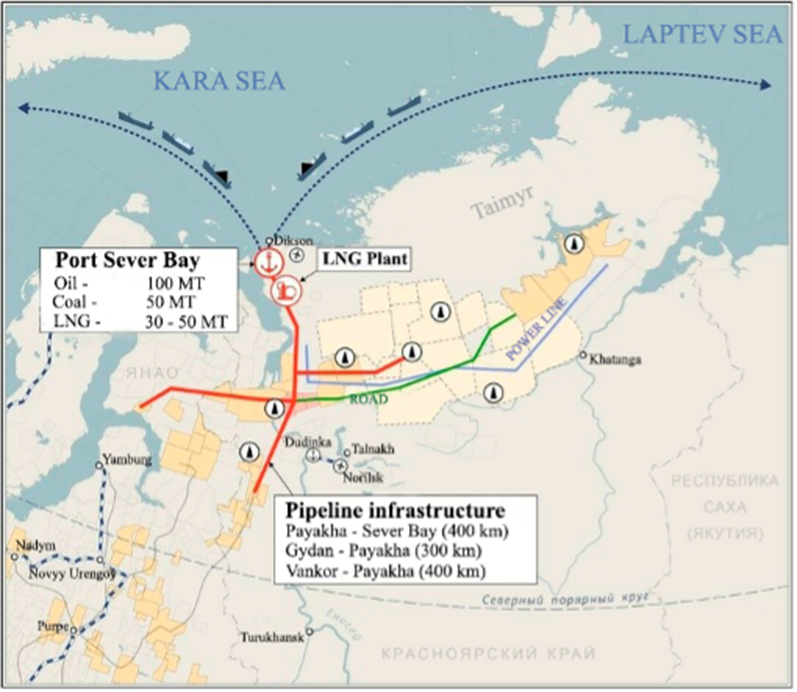

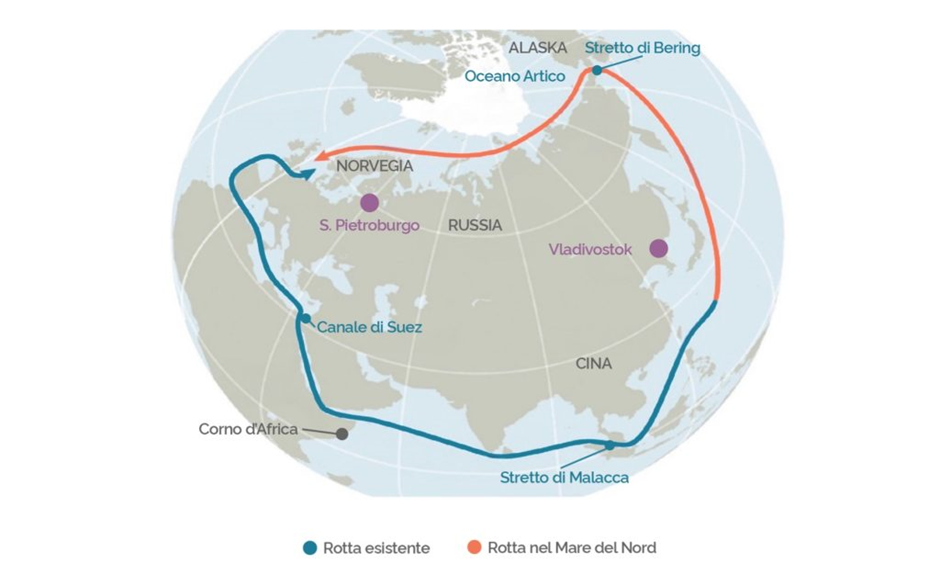

Regions such as Africa, Latin America and Asia-Pacific were particularly analyzed in terms of encouraging domestic energy companies to diversify their exports[xv]. Assuming that “Western Europe’s energy supply will continue to decline in the near future”, new oil and gas pipelines in Western and Eastern Siberia, notably the Power of Siberia and the Sakhalin-Khabarovsk-Vladivostok pipeline (Fig. 4), are being considered. These, plus the North Sea Route (Fig, 5) for the transportation of energy resources, including LNG in the Arctic (“one of the main products transported on and through the North Stream Route”[xvi] and oil (notably from the Van Kol/Vostok project – Fig. 6) as an alternative to transportation through the Arctic.

Fig. 5 – North Sea Route

Fig. 6 – Rosneft’s Vankor and Vostok projects

According to Aleksandr Novak, Deputy Prime Minister for Energy Affairs, “many countries in Latin America, Africa and other Asia-Pacific countries are interested in buying Russian oil products” [xvii]. Chinese and Indian oil imports have increased significantly in the last two years.

Russia’s identity as an energy superpower is reflected precisely in its relations with these two Asian countries: in 2023, Russia confirmed its position as the largest oil exporter to China. This position was to be maintained in 2024, as, of course, the December statistics show.

From January to November 2024, bilateral trade amounted to 222.78 billion US dollars, mainly in commodities. Given the war environment and Trump’s presidency, this amount will increase further in 2025.

In 2024, Gazprom exported a record amount of gas to China through the Siberian power project, and in 2025 Moscow and Beijing expect to reach the pipeline’s maximum capacity, estimated at around 38 billion cubic meters of gas[xviii]. In the calculation of bilateral trade volumes, which are higher than in the previous year, oil and natural gas certainly account for a large share.

But all is not rosy for the China-Russia energy partnership. The signing of the final contract to build the Power of Siberia 2 gas pipeline through Mongolia, with a total gas capacity of 50 billion cubic meters, continues to be postponed “for the time being.”[xix] The most likely reason for the postponement is the failure of Moscow and Beijing, as well as state-owned Gazprom and China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), to reach a final agreement on raw material prices. The project is absolutely necessary for redirecting and monetizing some of the gas previously exported from the Russian Federation to Europe through the Siberian oil fields and, ultimately, for strengthening Russia’s position as an energy superpower.

The same move, aimed at redirecting Russian energy flows from west to south, is underway with a special partner, India. This country is replacing China as the global engine of energy consumption, especially oil: by 2024, India will overtake China in oil imports from Russia by more than ten times, if not more[xx].

The consequences of this trend are very concrete and realistic. Russian-Indian energy interdependence has recently become even more pronounced thanks to new contracts signed between state-owned companies over more than a decade; these contracts, signed at the end of 2024, have in fact laid the foundations for a longer-term oil interdependence. The agreement to buy 500,000 barrels per day of oil between Russia’s Rosneft and India’s Reliance (both state-owned companies) is the largest oil deal between the two countries, valued at around $13 billion a year at current oil prices.

The article lists several hypotheses that suggest interesting changes in the energy interdependence between Moscow and New Delhi and trends in the oil market. Indeed, a comparison of the direction of the market over the last three years of the agreement even shows a reversal of bargaining power between Indian and Russian companies, despite the fact that both face embargoes and sanctions from the West[xxi].

In a phase of the market characterized by oil prices that are by no means exorbitant, Russian companies actually secure greater bargaining power in the absence of affordable alternatives on the Middle Eastern market. This is yet another example of how the dynamism and instability of the international energy and geopolitical situation affects Russia’s ability to build long-term interdependencies. On the other hand, there are also dynamics that directly affect Russia’s identity as an energy superpower, and their analysis and understanding can never be separated from the study of the global energy scenario.

References:

[i] C. Holbraad, Superpowers and International Conflict, London, Macmillan, 1979 – accessed: file:///C:/ /Users/lears/AppData/Local/Microsoft/Windows/INetCache/IE/LHFC0XME/b1414261844[1].pdf

[ii] P. Dukes, The Superpowers: A short history, Routledge, 2001 – accessed: https://www.scribd.com/document/518806840/Nhatbook-the-Superpowers-a-Short-History-Paul-Dukes-2001

[iii] P. Sharp, “Adieu to the superpowers?”, International Journal, vol. 38, 1992 https://www.jstor.org/stable/40202805?workspaceFolderId=6b2ff5c3-748e-485d-adee-5ff54f5e805f&orderBy=updatedOn&orderType=desc&index=0

[iv] R. Weitz, “Supowerpower Symbiosis: The Russia-China Axis”, World Affairs, vol. 175, no.4, 2012, pp. 71-78 – https://www.jstor.org/stable/40202805

[v] S. Rosefield, Russia in the21st Century: The Prodigal Superpower, Cambridge, 2004 – accessed https://assets.cambridge.org/97805218/36784/sample/9780521836784ws.pdf

[vi] Vladimir Ilyich Lenin – accessed: https://ro.wikiquote.org/wiki/Vladimir_Ilici_Lenin

[vii] A. Banerjee, “Electricity: Science Fiction and Modernity in Early Twentieth Century Russia”, Science Fiction Studies, vol. 30, no.1, 2003, pp. 49-71 – accessed: file:///C:/Users/lears/Downloads/Electricity_Science_Fiction_and_Modernit.pdf

[viii] Baev, Pavel – 2012/12/06 SN – 9780203932605 – Russian Energy Policy and Military Power: Putin’s Quest Greatness – downloaded from Google Play: https://play.google.com/store/books/details/Pavel_K_Baev_Russian_Energy_Policy_and_Military_Po?id=V8BBD1Kfp8wC

[ix] S. Bouzarovski and M. Bassin, “Energy and Identity: Imagining Russia as a Hydrocarbon Superpower”, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, vol. 101, no.4, 2011, pg. 783-94. – accessed: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232892276_Energy_and_Identity_Imagining_Russia_as_a_Hydrocarbon_Superpower

[x] V. Putin, “BRICS Plus/Outreach plenary session at the 16th BRICS Summit” – accessed: file:///C:/ /Users/lears/Downloads/energysuperpower.pdf

[xi] Страны ЕАЭС обссуждают проект энергокоридора из Росссиии через Казахстан вКиргизиию” (EEU countries discuss the project of an energy corridor from Russia through Kazakhstan to Kyrgyzstan) – accessed: https://cdn.finance.kz/news/strany-eaes-obsuzhdayut-proekt-energokoridora-iz-rossii-cherez-kazahstan-v-kirgiziyu

[xii] Triple gas alliance: role and place of Uzbekistan – view from Tashkent –

https://centralasianlight.org/news/triple-gas-alliance-the-role-and-place-of-uzbekistan

[xiii] Upstream, “Gazprom’s new land of plenty: Uzbekistan – accessed: https://www.upstreamonline.com/production/gazprom-s-new-land-of-plenty-uzbekistan/2-1-1715970?zephr_sso_ott=HHbGU6

[xiv] Gas pipeline project to China via Kazakhstan now underway – Novak – accessed: https://interfax.com/newsroom/top-stories/108838/

[xv] V. Putin, Meeting on current situation in oil and gas sector, President of Russia – accessed: https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/putin-says-russia-will-see-higher-oil-gas-revenues-coming-months-2023-04-11/

[xvi] Ibid

[xvii] Many countries want to buy Russian oil – Novak“, Tass, December 27, 2023 – accessed: https://tass.com/economy/1726967

[xviii] Russia’s Daily Pipeline Gas Flows to China Set New Record – Blumberg – accessed: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-12-21/russia-s-daily-pipeline-gas-flows-to-china-set-new-record

[xix] Russia and China plan to sign contract on Power of Siberia-2 in near future – accessed: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-12-21/russia-s-daily-pipeline-gas-flows-to-china-set-new-record

[xx] India surpasses China to become Russia’s top oil buyer in July – accessed: https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/india-surpasses-china-become-russias-top-oil-buyer-july-2024-08-22/

[xxi] India’s State Oil Refiners Struggle to Get Russia Crude Supplies – accessed: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-12-23/india-s-state-oil-refiners-struggle-to-get-russia-crude-supplies