| The Maritime Security Forum is pleased to provide you with a product, in the form of a daily newsletter, through which we present the most relevant events and information on naval issues, especially those related to maritime security and other related areas. It aims to present a clear and concise assessment of the most recent and relevant news in this area, with references to sources of information. We hope that this newsletter will prove to be a useful resource for you, providing a comprehensive insight into the complicated context of the field for both specialists and anyone interested in the dynamics of events in the field of maritime security. |

Navy: U.S. fighter jet falls off aircraft carrier and into Red Sea

MS DAILY BRIEF – APRIL 29 th, 2025

READ AND SHARE!

Daily appearance Monday-Saturday 10 AM (GMT +2)

Some information is presented when possible from several sources

Content

Power supply begins to return to Spain and Portugal after unprecedented blackout 1

Friedrich Merz chooses pro-Kyiv foreign minister and pledges Germany’s support for Ukraine. 3

Trump news in brief: children targeted by tough immigration measures. 5

Ukraine war update: Zelenskyy calls Putin’s short-term ceasefire offer “manipulation” 7

Head of Israel’s Shin Bet security service announces resignation after dispute with Netanyahu. 8

Jack Ma, co-founder of Alibaba, involved in a campaign of intimidation by the Chinese regime. 10

Romania to build 6 frigates for the Netherlands and Belgium – April 28, 2025. 13

New North Korean missile destroyer equipped with Russian weapons – April 27, 2025 14

Indian and Pakistani navies deploy as tensions rise – April 27, 2025. 16

The age of eternal wars. Why military strategy no longer brings victory. 17

India orders 26 Rafale fighter jets for €7.5 billion. 24

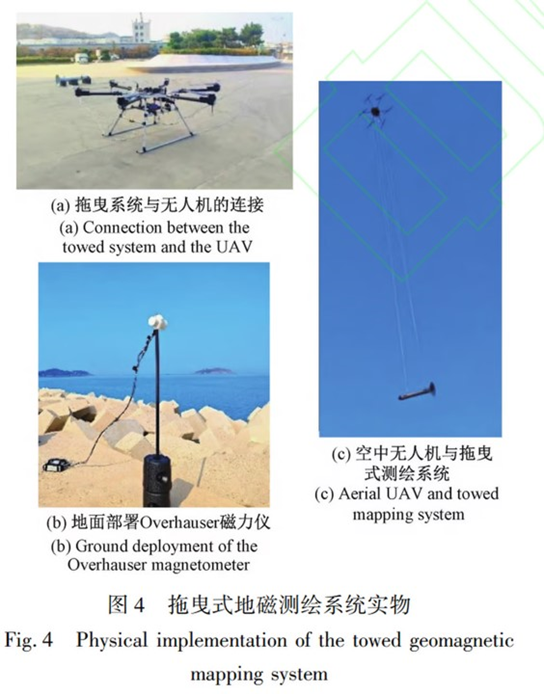

New Chinese technology allows drones to detect submarines – April 28, 2025. 26

JAS 39 Gripen Fighter has a “Made in USA” problem it can never escape – April 28, 2025 27

China is scared: Space forces race to finish first “space aircraft carrier” – April 28, 2025 29

Declining deterrence of America’s nuclear arsenal – April 28, 2025. 31

Royal Navy confirms Portsmouth Naval Base as home for new Type 31 frigate class. – Apr 28, 2025. 33

Naval tensions rise in Indo-Pacific as US and Chinese forces maneuver – April 28, 2025 35

How does the deployment of Carrier Strike Group 2025 benefit the UK?. 38

United Kingdom – How should the next national security strategy differ from integrated reviews?. 41

Power supply begins to return to Spain and Portugal after unprecedented blackout

The blackout, attributed by operators to temperature variations, left tens of millions of people without electricity

Sam Jones and Ashifa Kassam in Madrid, and Jon Henley

Tuesday, April 29, 2025, 12:24 a.m. CEST

Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez said that “everything possible” was being done overnight to restore power to all regions of the country after an unprecedented regional power outage left tens of millions of people on the Iberian Peninsula without electricity.

Late on Monday evening, Sánchez said that the aim was to restore power across Spain on Tuesday, adding that 50% of the national electricity supply had been restored in the last few hours.

The blackout, attributed by the Portuguese operator to extreme temperature variations, left the two countries without trains, subways, traffic lights, ATMs, telephone connections, and internet access.

People were stranded in elevators, trains, traffic, and abandoned at airports. Hundreds of people stumbled through subway tunnels in pitch darkness, using their cell phone flashlights; others crowded into supermarkets that were accepting only cash to buy basic goods or set out on the long journey home.

Mobile phone networks went down and internet access was cut off when the power went out at 12:33 p.m. (11:33 a.m. BST). Hospitals postponed routine operations but used generators to deal with critical cases, and although electronic banking services operated on backup systems, most ATM screens were blank.

In scenes reminiscent of the 2003 blackout that caused widespread power outages in the northeastern US, rail services on the Iberian Peninsula were halted, air traffic was disrupted, and traffic lights went out. Hundreds of people had to be rescued from stuck elevators.

Travelers were stranded as the power outage affected most forms of transportation. Photo: José Jordan/AFP/Getty Images

Madrid Mayor José Luis Martinez-Almeida urged people to minimize travel and stay where they were, adding, “It is essential that emergency services are able to move around.” Play at the Madrid Open tennis tournament has been suspended.

Sánchez said it was still too early to know what caused the outage, but that no possibilities were being ruled out.

“How long it will take to return to normal is something that [national grid operator] Red Eléctrica cannot yet say with certainty,” he said. “There has never been a complete blackout before and the idea now is to continue with the gradual and cautious restoration of power to avoid any setbacks in the coming hours.”

On Monday at 10 p.m. local time, 62% of Spain’s substations were back in operation (421 out of 680) and 43.3% of electricity demand was being met, while Portugal’s grid operator, REN, said it had restored power to 85 of the country’s 89 substations.

Red Eléctrica had previously warned that it could take between six and ten hours to fully restore power after what it called an “exceptional and totally extraordinary” incident.

Along a major thoroughfare in Madrid’s Argüelles neighborhood, the restoration of power sparked cheers and sincere applause among many people walking down the street.

Sánchez said the power outage occurred at 12:33 p.m., when, for five seconds, 15 gigawatts of the energy produced — equivalent to 60% of all energy consumed — suddenly disappeared.

“This is something that has never happened before,” he added. “The cause of this sudden power outage has not yet been determined by experts. But they will… All potential causes are being investigated and no hypothesis or possibility is being ruled out.”

Portuguese operator REN said the outage was caused by a “rare atmospheric phenomenon,” with extreme temperature variations in Spain causing “abnormal oscillations” in high-voltage lines.

REN said the phenomenon, known as “induced atmospheric vibrations,” caused “synchronization failures between electrical systems, leading to successive disturbances in the interconnected European network.”

Large-scale outages are unusual in Europe. In 2003, a problem with a hydroelectric power line between Italy and Switzerland caused power outages for about 12 hours, and in 2006 an overloaded power grid in Germany caused power outages in parts of the country and in France, Italy, Spain, Austria, Belgium, and the Netherlands.

Sánchez thanked France and Morocco for providing additional electricity to Spain and said that the current deficit would be mitigated by using gas and hydroelectric power.

The prime minister said that additional police and Civil Guard officers had been mobilized across the country to ensure public safety during the night, adding that hospitals were functioning well thanks to the efforts of medical staff.

He said that telecommunications services were still experiencing disruptions, mainly due to a lack of power supply to antennas.

Sánchez said that only 344 of the 6,000 flights in Spain had been canceled on Monday and that the country’s road network was functioning well, except for some traffic jams.

The main traffic disruptions were on the rail network, where 35,000 passengers stranded in more than 100 trains were assisted by rail companies and the military emergency unit. Another 11 trains that had stopped in remote areas were still waiting for assistance.

In Madrid and other cities, traffic lights stopped working, causing gridlock as vehicles slowed down to avoid collisions, and the metro was shut down. Spain’s national road authority, the DGT, urged drivers to avoid using the roads as much as possible.

The newspaper El País published photos and videos on its website showing passengers traveling through dark subway tunnels in the Spanish capital and police directing traffic on city streets. The images also showed the newspaper’s reporters working by flashlight.

The Spanish Ministry of Health said in an update on social media that it was in contact with regional authorities to assess the extent of the widespread power outage, but assured the public that hospitals had backup systems in place.

In Portugal, the power outage affected the capital, Lisbon, and surrounding areas, as well as the northern and southern parts of the country. Subway cars in Lisbon were evacuated, and ATMs and electronic payment systems were disrupted.

Portuguese water supplier EPAL said water supplies could be cut off, leading to queues at shops as people rushed to buy bottled water and other emergency supplies such as gas lamps, generators, and battery-powered radios.

Shops were stormed by people looking for emergency items such as flashlights and radios. Photo: Adri Salido/Getty Images

Sánchez said that eight of Spain’s 17 autonomous regions — Andalusia, Castilla-La Mancha, Extremadura, Galicia, La Rioja, Madrid, Murcia, and Valencia — had declared a level 3 state of emergency, with responsibility for intervention falling to the central government. He said schools in these areas would be open on Tuesday but would not hold normal classes.

He said the situation across the country remained very “asymmetrical” on Monday evening, with some regions already having 90% of their electricity restored, while others had recovered less than 15%.

Sánchez also advised non-essential workers to stay home on Tuesday if necessary.

“It will be a long night,” he said. “But we will continue to work to return to normal as quickly as possible.”,,,,

Friedrich Merz chooses pro-Kyiv foreign minister and pledges Germany’s support for Ukraine

Chancellor-designate vows to combat Russian aggression and appoints Johann Wadephul, a former soldier, to a key post

Kate Connolly in Berlin

Monday, April 28, 2025, 7:32 p.m. CEST

German Chancellor-designate Friedrich Merz has promised to provide firm support for Ukraine within his government after announcing that a pro-Kyiv foreign policy expert and former soldier will be the new foreign minister.

A few days before taking office, Merz said on Monday that “this is not the time for euphoria,” as his conservative CDU party met to approve an agreement to form a coalition government with the Social Democrats.

Promising to combat Russian aggression and the rise of the far right, he told party colleagues: “The pillars on which we have relied in recent years and decades are crumbling around us. Confidence in our democracy is shaken as never before in our country’s post-war history.”

Merz, a former banker, said that Johann Wadephul, a conservative lawmaker who has long advised Merz on foreign policy, would become the new foreign minister.

Wadephul has been a supporter of military aid to Ukraine and recently told the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ) newspaper that the war in Ukraine “is not about a few square kilometers of Ukraine, but rather the fundamental question of whether we will allow a classic war of conquest in Europe.”

Merz said that despite internal reservations about Germany’s role in Ukraine, with some calling for an end to arms deliveries, there was “no ifs or buts” about continuing support. Vladimir Putin’s invasion, he said, was nothing less than a fight “against the entire political order of the European continent.”

He stressed that Germany would remain “on the side of this attacked country and thus on the side of all people in Europe who are committed to democracy and the rule of law… to freedom and an open society.”

His statement came hours after Boris Pistorius, a Social Democrat who is expected to continue as defense minister, said Donald Trump’s peace deal proposals were “akin to a surrender.”

Pistorius and Wadephul will work closely together in a newly formed national security council that will represent Germany on the European and international stage.

Alluding to Trump without naming him, Merz said on Monday: “We have come to the conclusion that we can no longer be sure of transatlantic relations in the spirit of freedom and order based on rules.”

Merz and his government are set to be sworn in by parliament on May 6, ending a six-month political stalemate. The conservative CDU/CSU alliance agreed on a coalition deal with the Social Democrats (SPD) after winning the February 23 federal election, in which the far-right populist Alternative for Germany (AfD) party came in second.

The results of a poll of the SPD’s 365,000 members approving the agreement are expected on Wednesday. Only after they give the green light will the SPD announce its cabinet ministers, party co-leader Lars Klingbeil said.

In recent months, amid a sense of stagnation and growing discontent across the country, the AfD has risen in the polls and is now, for the first time, ahead of the conservatives.

Merz has pledged to reduce the AfD, which he said had managed to capitalize on people’s fears and insecurity, to the “marginal phenomenon” it once was. He said he would do so by combating “unregulated” immigration that had “got out of control” over the past decade, an allusion to his predecessor Angela Merkel’s so-called open-door policy, during which around 1 million refugees came to Germany.

Among his surprise appointments is Karsten Wildberger, the CEO of Ceconomy, the parent company of German electronics retailers Saturn and Mediamarkt, who will head a new ministry for digitalization and state modernization.

He will be partly responsible for deciding how to spend a special fund of billions of euros – controversially approved by the outgoing government to boost Germany’s ailing infrastructure and economy, as well as to strengthen its defense forces.

Trump news in brief: children targeted by tough immigration measures

The measures have sparked concerns about what one critic called “family separation through the back door” — top US political stories for Monday, April 28.

The Guardian team

Tuesday, April 29, 2025, 4:16 a.m. CEST

As part of President Donald Trump’s radical campaign to combat immigration, unaccompanied minors are now being targeted for deportation, with the Department of Homeland Security conducting “social checks” on children who have arrived in the US alone, usually via the border with Mexico.

The measures have sparked fears of a crackdown and raised alarm about what one critic called “family separation by the back door.”

The president also signed two executive orders related to immigration, including one targeting so-called “sanctuary cities” that “obstruct the enforcement of federal immigration laws.”

Here is a summary of the main news:

Unaccompanied immigrant children could be deported or prosecuted

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officials are searching for unaccompanied immigrant children in nationwide operations with the aim of deporting them or opening criminal cases against them or the adults who are legally sheltering them in the US, according to sources and an ICE document.

Trump signs executive order requiring list of sanctuary cities and states

Donald Trump signed two new executive orders related to immigration on Monday afternoon, according to the White House, including one targeting so-called “sanctuary cities” and another that the administration says will strengthen law enforcement.

Peace Corps to suffer “significant” cuts after Doge review

The Peace Corps is offering staff a second option to buy out their contracts, according to a source familiar with the matter. Allison Greene, the Peace Corps’ executive director, sent an email to staff on Monday with an update on the agency’s review by the “Department of Government Efficiency” (Doge).

Doge’s conflicts of interest amount to $2.37 billion, according to Senate report

Elon Musk and his companies face at least $2.37 billion in legal exposure due to federal investigations, litigation, and regulatory oversight, according to a new report from Senate Democrats. The report attempts to quantify Musk’s numerous conflicts of interest through his work with the so-called “Department of Government Efficiency” (Doge), warning that he may try to use his influence to avoid legal accountability.

Trump appointees at the Justice Department remove leadership of voting unit

People appointed by Donald Trump to the Justice Department have removed all senior civil servants working as managers in the department’s voting division and ordered lawyers to classify all active cases, according to people familiar with the matter, as part of a broader attack on the department’s civil rights division.

Democrats warn that budget cuts to the US’s top labor watchdog will be “catastrophic”

Democrats have warned that budget cuts to the US’s top labor watchdog threaten to make the organization “effectively ineffective” and will be “catastrophic” for workers’ rights. Elon Musk’s company Doge has targeted the National Labor Relations Board for budget cuts and terminated leases in several states.

JB Pritzker’s fiery speech calling for mass protests sparks talk of 2028 candidacy

Illinois Democratic Governor JB Pritzker harshly criticized the Trump administration, calling for “mass protests” and saying Republicans “can’t know a moment of peace” during a fiery speech in New Hampshire that immediately sparked speculation about a presidential run. Read the full article

An Irish woman who has lived legally in the US for four decades was detained by immigration authorities because of a criminal record dating back nearly 20 years.

- An Irish woman who has been living legally in the USfor four decades has been detained by immigration authorities because of a criminal record dating back nearly 20 years.

- Senior British government officials have askedgolf bosses to host the 2028 Open Championship at Donald Trump’s Turnberry golf course after repeated requests from the US president, sources said.

- A number of CBS’s 60 Minutes presenters have criticizedthe show’s owners in a dispute over journalists’ independence, amid a lawsuit filed by Trump and an attempted sale.,,,

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/apr/29/trump-administration-news-updates-today

Ukraine war update: Zelenskyy calls Putin’s short-term ceasefire offer “manipulation”

The Ukrainian president is calling for a month-long truce after Russia proposed a three-day ceasefire to mark the victory in World War II. What we know on day 1,161

Guardian staff and agents

Tuesday, April 29, 2025, 3:41 a.m. CEST

- Volodymyr Zelenskyy has called for an immediate one-month ceasefire after Vladimir Putin unilaterally announced a three-day ceasefire for next month to mark the anniversary of World War II. The Ukrainian president said: “Now there is a new attempt at manipulation. For some reason, everyone has to wait until May 8 and only then declare a ceasefire to ensure calm for Putin during the parade.” He added: “We value people’s lives, not parades. We believe that the world sees no reason to wait until May 8. And the ceasefire should not last just a few days, only for the killings to resume.”

- Ukrainian officials also pointed out that Russia had announced a similar ceasefire during Easter, only to violate it. The Russian president suggested a ceasefire in May to mark the 80th anniversary of the Soviet Union’s victory in World War II, and said that Kiev should follow Moscow’s example.

- If observed by both sides, it would be the first complete ceasefire since the Russian invasion of Ukraine began more than three years ago.

- A series of explosions were heard in Kiev in the early hours of Tuesday after Ukrainian air forces issued air raid alerts for the capital, a Reuters witness reported. The Ukrainian army said air defense systems were trying to repel an air attack.

- New German Chancellor Friedrich Merzhas promised to give firm support to Ukraine at the heart of his government after announcing that a pro-Kyiv foreign policy expert and former soldier will be the new foreign minister. Merz said Johann Wadephul, a conservative lawmaker who has long advised Merz on foreign policy, would become the new foreign minister. Wadephul has been a supporter of military aid to Ukraine and recently told the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ) newspaper that the war in Ukraine “is not about a few square kilometers of Ukraine, but rather the fundamental question of whether we will allow a classic war of conquest in Europe.” Merz himself said that Vladimir Putin’s invasion is nothing less than a fight “against the entire political order of the European continent.” Boris Pistorius, a Social Democrat who is expected to continue as defense minister, said Donald Trump’s peace deal proposals were “akin to capitulation.”

- US Secretary of State Marco Rubio told his Russian counterpart Sergei Lavrov that the US is committed to working to end “this senseless war,” the State Department said. “The United States is determined to facilitate an end to this senseless war,” State Department spokeswoman Tammy Bruce said in a statement on Sunday’s phone call, which had already been announced by Russia. She said Rubio discussed with Lavrov “the next steps in the peace negotiations between Russia and Ukraine and the need to end the war now.” The call took place before Putin offered a three-day ceasefire on Monday.

- Luke Harding, a reporter for The Guardian newspaper, reported from the front lines near the Oskil River in Ukraine. “Before the war, it was a place of recreation. Visitors would grill kebabs on the sandy beaches or kayak past a string of low chalk hills and a small national park. Now it is a war zone, with fighting involving drones, artillery, and bombs. The Russians are trying to extend a narrow bridgehead on the right bank of the river, near Dvorichna,” he writes. Read the full article here.

Head of Israel’s Shin Bet security service announces resignation after dispute with Netanyahu

Ronen Bar will leave office in June after being dismissed by the prime minister, but the decision was blocked by the Supreme Court

Jason Burke in Jerusalem

Monday, April 28, 2025, 9:53 p.m. CEST

Ronen Bar, head of Israel’s Shin Bet internal security service, has said he will resign in less than two months after weeks of tension with Benjamin Netanyahu, who tried to fire him, bringing Israel to the brink of a constitutional crisis.

“After 35 years of service, in order to allow for an orderly process of appointing a permanent successor and for a professional handover of the position, I will end my term on June 15, 2025,” Bar said Monday at a Shin Bet memorial ceremony.

The battle between Netanyahu and Bar intensified after the Supreme Court blocked a cabinet decision to dismiss Bar from office — the first Shin Bet chief to be fired.

Netanyahu said he had lost confidence in Bar’s ability to lead Shin Bet and accused him of conflict of interest and politicizing the agency.

Bar’s decision to resign will now spare the Supreme Court from issuing a potentially controversial and divisive ruling.

Last week, in a 31-page statement to the Supreme Court, Bar, 59, claimed that Netanyahu had tried to fire him because he refused to declare his loyalty to the prime minister in court and had tried to use the agency to spy on anti-government protesters.

Netanyahu filed his response to the court on Sunday, rejecting Bar’s allegations. He repeatedly referred to a “deep state” in Israel that he said was trying to thwart democratically elected leaders and undermine elected governments.

The relationship between Netanyahu and Bar, a former special forces soldier and graduate of Tel Aviv and Harvard universities, deteriorated after the publication in March of a Shin Bet report on the October 7, 2023, attacks by Hamas militants in southern Israel. The service acknowledged mistakes but criticized the Netanyahu government’s policies, which it said had allowed Hamas to consolidate its power in Gaza and take Israel by surprise.

Could the West Bank become the next Gaza? – video explanation

Netanyahu has never taken responsibility for Israel’s worst national security disaster, which killed 1,200 people, mostly civilians, and led to the kidnapping and hostage-taking of 251 people in Gaza. Eighteen months after the attack, many of the senior officials who were in office at the time have resigned or been dismissed. Netanyahu seems unlikely to leave power before elections at the end of next year and could remain in office beyond that.

The Bar’s authorization for Shin Bet to open two investigations into close associates of Netanyahu, including one into alleged payments from Qatar to promote its interests in Israel while Qatar was partially funding Hamas in Gaza, was widely cited as the reason for his dismissal. Netanyahu already faces a slew of corruption charges in court, and political opponents have claimed that the prime minister wanted to remove Bar to sabotage the investigations.

Netanyahu has consistently denied any improper or hidden motives for Bar’s dismissal.

“To date, the reason for my dismissal is not clear to me,” Bar wrote in his sworn statement to the Supreme Court. “But… it was not based on any professional criteria, but was determined by Netanyahu’s expectation that I would be personally loyal to him.”

Yair Lapid, the Israeli opposition leader, praised Bar’s decision and criticized Netanyahu. “Of those responsible for the biggest failure in the country’s history, only one remains, clinging to his seat,” Lapid said.

The Shin Bet’s priority is fighting terrorism, but the service also investigates espionage, manages security clearances for thousands of sensitive positions, and has a legal duty to defend Israel’s democratic system.

Bar took over the service in 2021, appointed by then-Prime Minister Naftali Bennett, and was expected to serve the standard five-year term.

Bar was one of the first senior security officials to take responsibility for the numerous failures that led to the 2023 attacks and made clear that he intended to resign.

He stayed on for so long, his associates and supporters said last month, to work on securing the release of hostages still held by Hamas in Gaza and to protect the Shin Bet from political maneuvering.

,,, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/apr/28/ronen-bar-israel-shin-bet-resignation-netanyahu-row

Jack Ma, co-founder of Alibaba, involved in a campaign of intimidation by the Chinese regime

The billionaire appears to have been asked to pressure a friend to return to China and help prosecute a disgraced official

Maeve McClenaghan and Tom Burgis

Tuesday, April 29, 2025, 6:00 a.m. CEST

The Chinese regime has recruited Jack Ma, the billionaire co-founder of Alibaba, in a campaign to intimidate a businessman into helping purge a senior official, documents seen by the Guardian suggest.

The businessman, who can only be named as “H” for fear of reprisals against his family still in China, was subjected to a series of threats from the Chinese state in an attempt to force him to return home from France, where he was living. These included a series of phone calls, the arrest of his sister, and the issuance of a red notice, an international alert, through Interpol.

The climax came in April 2021 with a phone call from Ma. “They said I was the only one who could convince you to come back,” Ma said.

H, who had known Ma for many years, recorded the call. He had done the same with calls from other friends, as well as from Chinese security officials who had called him in the previous weeks, all with the same message.

Transcripts of these calls, presented in a French court along with other legal documents, offer a rare insight into some of the methods used by the Chinese regime to exert its influence around the world. The documents detail how a combination of threats, co-opted legal mechanisms, and extrajudicial pressure are used to control even people outside the country’s borders.

The findings are part of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) project “China Targets,” in which journalists have documented the methods used by the Chinese regime to track and crush dissent abroad. The team includes The Guardian, Radio France, and Le Monde, which obtained the transcripts and other legal documents.

A spokesperson for the Chinese embassy in the UK said: “The so-called ‘transnational repression’ by China is a pure fabrication.”

The threat of extradition

H, 48, a Chinese citizen born in Singapore, was in Bordeaux, France, when he received the call from Ma. A year earlier, Chinese police had issued an arrest warrant for H for financial crimes. China then issued an international arrest warrant through Interpol’s criminal alert system. French authorities confiscated his passport while considering his extradition.

Transcripts show that during the phone call, Ma suggested to H that all his problems would disappear if he helped him in the prosecution of Sun Lijun, a Chinese politician who had fallen out of favor with the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Sun was being prosecuted for bribery and stock market manipulation. “I’m doing all this for Sun, not for you,” Ma told him.

Sun, a former deputy security minister, was tasked in 2017 with overseeing security in Hong Kong during mass protests against Beijing’s crackdown on democratic freedoms. He had been arrested a year before H began receiving the phone calls. The Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) subsequently denounced Sun for “extremely exaggerated political ambitions” and “arbitrary disagreement with central political guidelines.”

He became one of many senior officials caught up in President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign, which human rights groups have said serves as a tool for Xi to eliminate political rivals.

“You have no other choice”

The transcript of the conversation suggests that Ma was unhappy about being involved in the deal. “Why did you get me involved in this?” he asked H.

Like Sun, Ma had fallen out of favor with Xi’s regime. After giving a speech in October 2020 criticizing China’s financial regulators, he was repeatedly sanctioned, including a $2.8 billion fine, and disappeared from public view.

The phone call to H was made six months later. Ma explained in the call that he had been contacted by Chinese security officials. “They spoke to me very seriously,” Ma told H. “They said they guarantee that if you come back now, they will give you the chance to be exempted… You have no other choice… the noose is tightening.”

Later, Ma called H’s lawyer to reiterate the message.

H did not return to China, and his lawyers challenged his extradition in the French courts.

Clara Gérard-Rodriguez, one of H’s lawyers, said: “We knew that if H returned to China, he would be arrested, detained, probably tortured until he agreed to testify… and that most of his assets, his company shares, would most likely be transferred to other people.”

The conviction rate in criminal cases in China is 99.98%, according to Safeguard Defenders, an organization that investigates abuses committed by the Chinese regime. It has documented how enforced disappearances and torture are endemic within the judicial system.

The money laundering charges brought against H in China a year before Ma’s appeal were linked to his connection with a credit platform, Tuandai.com. The founder of this company was sentenced to 20 years in prison for illegal fundraising. Chinese police believed he had tried to hide some of the embezzled funds when the investigation began. H, who had invested in the company, was accused of helping to transfer some of the money abroad through companies he controlled.

H’s lawyers told French courts that there was no evidence that he knew the source of the funds was dubious. In a phone call with a friend, recorded in French court documents, H maintained his innocence. “None of this is true,” he said.

The Chinese government issued an international arrest warrant for H through Interpol, the international police organization. This warrant flagged him as a potential criminal to police forces around the world and banned him from traveling. “It’s like a pin stuck in a butterfly,” said Ted R Bromund, an expert on legal cases involving Interpol procedures. “It keeps someone in place, locks them in, so they can’t escape.”

Although international arrest warrants are used against dangerous criminals, activists have long warned that they can be abused. British lawyer Rhys Davies recently told a government inquiry into transnational repression that international arrest warrants are “systematically and abusively used by autocratic regimes to target dissidents and opponents abroad.” He described the system as “the autocrat’s sniper rifle, because it acts from a distance, is precise and very effective.”

Although other countries, including Russia, Turkey, and Rwanda, are known for abuses under this system, China’s tactics are different, according to experts. Instead of relying on extradition, Chinese authorities use Interpol to locate individuals, then ramp up pressure, threatening them and their family members in their home country until the person agrees to return “voluntarily.”

An Interpol spokesperson said that this system has led to the arrest of thousands of the world’s “most dangerous criminals” every year. He added: “Interpol knows that red notices are powerful tools for law enforcement cooperation and is fully aware of their potential impact on the individuals concerned, which is why we have robust, evaluated, and continuously updated processes in place to ensure that our systems are used appropriately.”

“Psychological warfare”

While H waited in France, caught up in the legal process triggered by the red notice, he received calls from friends and security officials in what his lawyers called “total psychological warfare.” Sometimes the tone was friendly, with promises that all charges would be dropped; other times it was more threatening.

Transcripts of phone calls with the deputy investigator of the unit pursuing Sun, Wei Fujie, suggest that he promised H that if he returned, he would “not be prosecuted and the red notice would be canceled.”

A friend called H and told him, “In three days, your whole family will be arrested!” A few days later, H’s sister was arrested in China.

His case is far from unusual. The ICIJ’s “China Targets” project has recorded details of 105 targets of China’s transnational repression in 23 countries. Half of them said that their family members in their country of origin had been harassed through intimidation and interrogation by police or state security officials.

Rehabilitation

When H’s case came before the Bordeaux Court of Appeal in July 2021, the court rejected the extradition request. Subsequently, the arrest warrant was removed from Interpol’s systems. H’s lawyers successfully argued that the extradition request had been issued for political reasons, to compel him to testify against Sun.

Sun was convicted of stock market manipulation, bribery, and other crimes, without H’s involvement in the trial. He was given a suspended death sentence.

H, who was unable to trade or work in China, was unable to pay his loans or rent on a luxury property and ran up debts totaling $135 million, according to Chinese media reports. He declined to comment when approached by the Guardian.

A spokesperson for the Chinese embassy in the UK said: “China always respects the sovereignty of other countries and cooperates with other countries in law enforcement and justice in accordance with the law.”

Ma’s representatives raised questions about his identity in the calls. The Guardian spoke to H’s lawyers, who said they had known the billionaire for many years before the call and had no doubt that the caller was Ma. During the legal proceedings in which his lawyers challenged the arrest warrant, no questions were raised about the identity of the callers.

Ma did not respond to The Guardian.

Earlier this year, he was seen applauding Xi enthusiastically at a business leaders’ meeting in Beijing’s Great Hall of the People — a sign, according to local media, of the billionaire’s public rehabilitation.

Gérard-Rodriguez, H’s lawyer, said: “We saw and learned publicly about Jack Ma’s disappearance… this man, considered untouchable, extremely powerful, extremely well connected in all countries of the world, disappeared completely for several months and then reappeared, swearing allegiance to the Chinese Communist Party.

“And in the end, the same thing happened to H… that he would return to show his loyalty, to show whose side he is on.”

Romania to build 6 frigates for the Netherlands and Belgium – April 28, 2025

Frigates for Belgium and the Netherlands will be built in Galați, Romania. The countries have ordered six ships, which will be distributed between them.

This was stated by Gheorghe Savu, director of Damen Naval Romania.

The order for six ships is part of a plan to strengthen the military capabilities of the European Union.

Construction of the six frigates will begin this summer at the Damen shipyard in Galați. Delivery is scheduled for 2028-2032.

Belgium and the Netherlands ordered the ASWF anti-submarine frigates in June 2023, with shipbuilder Damen and Thales as subcontractors.

The order for new frigates for Belgium and the Netherlands is part of the Future Surface Combatant project.

Future Surface Combatant is a project of the Dutch and Belgian navies to replace the aging Karel Doorman-class multi-role frigates.

The future frigates will replace the HNLMS Van Amstel and HNLMS Van Speijk in the Dutch navy and the Leopold I and Louise-Marie in the Belgian navy.

The main task of the anti-submarine frigates is to detect and destroy submarines from a distance.

This is done, among other things, with the ship’s NH90 helicopter. Both the frigate and the helicopter can launch a Mk54 torpedo to neutralize the submarine.

MK 54 light torpedo. Photo from open sources

Damen began investing in the Romanian shipyard in Galați in 1999 to build such large ships.

Today, the shipyard is one of the largest production facilities in the Damen Group, covering 55 hectares and employing approximately 1,500 people in the region, as well as subcontractors. Since joining the Damen Group, the shipyard has delivered over 500 ships.

Source: here

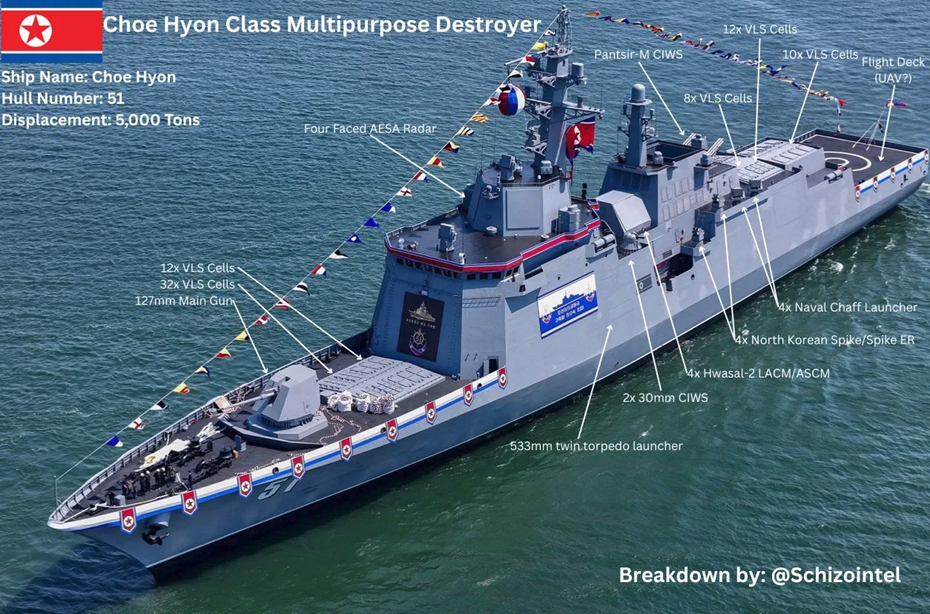

New North Korean missile destroyer equipped with Russian weapons – April 27, 2025

Russian weapons systems have been spotted on North Korea’s latest missile destroyer, including an air defense system and what appear to be anti-submarine missiles.

The discoveries were noted by North Korean military observer Tarao Goo @NK Watcher on his X account.

Among the weapons, Goo identified a missile similar to the Russian 91RE1 anti-submarine missile based on its visual characteristics.

However, due to the angle of the photos, a definitive identification was not possible. It remains possible that the missile is a previously unknown North Korean development.

The Russian 91RE1 missile, part of the Otvet anti-submarine system, is launched from 533 mm torpedo tubes—such tubes are visible on the new destroyer.

It is therefore possible that the missile is part of the ship’s arsenal or that of a new North Korean nuclear submarine. Although no definitive identification can be made, the missile’s design appears to be borrowed from the Russian model. The photos also clearly show the Russian Pantsir-M or Pantsir-ME air defense system mounted on the stern of the destroyer.

The new North Korean destroyer

North Korea recently held a launch ceremony for its first new-generation multi-purpose missile destroyer. The event took place on April 25, 2025, at a shipyard in Nampo, where the ship was built.

The construction process took a record 400 days, reflecting an intensification of North Korea’s naval modernization efforts.

The new destroyer is officially classified as a 5,000-ton multi-purpose ship with an extensive missile arsenal.

A key feature of the ship is the presence of two types of vertical launch systems: larger cells for long-range attack missiles and smaller ones for air defense missiles, totaling 74 launch cells.

An inspection of the destroyer’s armament revealed a 127 mm automatic naval gun for attacking surface and coastal targets. For close-range defense, the ship is equipped with an anti-aircraft artillery system similar to the Soviet AK-230 and AK-360 systems, alongside the Russian Pantsir-ME.

The armament of the new North Korean multi-purpose destroyer Choe Hyon. Photo credit: KCNA/Intelschizo

Two 533 mm torpedo tubes are installed on both sides of the ship, partially concealed by radar-absorbing structures. The ship’s suite of sensors and radars includes four panel antennas, probably based on active phased array radar technology.

Additional radar antennas at the bow and stern, possibly used for anti-aircraft missile guidance, suggest an air defense approach similar to the Russian Tor system, which uses radio command guidance.

Finally, it is worth noting that unknown electronic warfare systems are also mounted near the ship’s main antenna masts.

Pantsir-M

Pantsir-M is a Russian missile and gun air defense system designed to defend surface ships against modern air threats, including small and low-flying unmanned aerial vehicles. It is based on the Pantsir-S ground system.

The complex has a modular structure, including a command module and up to four combat modules, which are located depending on the class and layout of the ship.

The Russian Pantsir-ME system. Photo credit: roe.ru

The modular system includes a command module and up to four combat modules, configured based on the ship’s design.

Each combat module has two 30 mm automatic cannons with six barrels, eight launch tubes for surface-to-air missiles, guidance units, and an optical radar control system.

The missile’s range is up to 20 km, with a maximum interception altitude of 15 km. The artillery system is effective up to 4 km.

91RE1 missile

The 91RE1 is a Russian anti-submarine missile designed to engage modern submarines—including nuclear attack submarines—at various depths and positions.

The missile is 7.65 meters long, 533 mm in diameter, and weighs approximately 2,050 kg. Its warhead is either a high-speed self-guided APR-3ME torpedo or a small MPT-1UME torpedo.

It can be launched from depths of 20 to 150 meters while the submarine is traveling at speeds of up to 15 knots. The missile’s range is 5 to 50 km when launched from a depth of 20-50 meters and up to 35 km from 150 meters.

Preparation before launch takes approximately 10 seconds. Up to four missiles can be launched in a salvo against a single target.

After launch, a solid-fuel booster propels the missile from under the water to altitude. The booster then separates, and the second stage continues along a controlled trajectory to the target area, guided by an inertial navigation system.

Source: here

Indian and Pakistani navies deploy as tensions rise – April 27, 2025

Following a terrorist attack in Indian-controlled Kashmir in which 26 tourists were killed by armed men, both India and Pakistan have put their forces on alert in anticipation that India will launch retaliatory strikes and that Pakistan will respond.

The attack in the Anantnag district of southern Kashmir was the first such act of terrorism since October 2001, when terrorists killed 35 people outside the Jammu and Kashmir state legislature. But tension between India and Pakistan over the status of Jammu and Kashmir has existed since independence, when, after fighting, a de facto border was established, leaving most of the province in Indian hands. The two countries then fought wars in 1947-1948, 1965, 1971, and 1999, with the status of Jammu and Kashmir being the main source of dispute. The first two wars were evenly matched, with India gaining numerical control in 1971 and 1999.

India suspended the Indus Water Treaty, which governs the sharing of river waters; expelled Pakistani citizens and defense personnel; and closed border crossings. Pakistan responded with similar measures.

Since Pakistan matched India’s nuclear capability in 1988, both countries have had to balance the desire to take strong military action with the risk that fighting could escalate out of control and threaten the use of nuclear weapons.

Naval warfare played a major role in the 1971 war, with Indian aircraft crippling Pakistan’s naval presence in the east, while the Pakistani navy in the west was largely neutralized by missile strikes. The Pakistani submarine PNS/M Hangor (S-131) managed to sink the Indian frigate INS Khukri (F149) and damage a second, INS Kirpan (F144). In the 1999 war, India successfully imposed a naval blockade on Pakistan’s main port of Karachi, and the lack of imported fuel was a factor that led Pakistan to accept the ceasefire that ended the war.

If relations deteriorate further, the Indian Navy is likely to try to impose another naval blockade as a passive option, with a lower risk of escalation. While most deployments will be kept secret, the Indian Navy’s aircraft carrier INS Vikrant (R11) was spotted off the coast of Goa on April 23. The Indian Navy also has five operational Kilo-class submarines and up to ten smaller Scorpene and Type-209 diesel-electric attack submarines.

Pakistan has issued a NOTAM (Notice to Airmen/Seamen) for the Arabian Sea and initiated a live-fire naval exercise, blocking a large maritime area at the border of the exclusive economic zone between the two countries and covering the maritime approach from Karachi. Pakistan can deploy up to eight French Agosta-70 and Agosta 90B submarines.

Potentially, both Indian and Pakistani precautionary naval deployments could affect commercial traffic, although international shipping lanes can be adjusted southward to avoid potential conflict zones.

Source: here

The age of eternal wars. Why military strategy no longer brings victory

Coalition forces in Bagram, Afghanistan (2002)

In Operation Desert Storm, the 1991 campaign to liberate Kuwait from Iraqi occupation, the United States and its coalition allies unleashed massive land, air, and sea power. It was over in a matter of weeks. The contrast between the United States’ exhausting and unsuccessful war in Vietnam and that of the Soviet Union in Afghanistan could not have been starker, and the quick victory even led to talk of a new era of warfare—a so-called revolution in military affairs. From now on, the theory went, enemies would be defeated through speed and maneuver, with real-time information provided by smart sensors guiding immediate attacks using smart weapons.

These hopes proved short-lived. The West’s counterinsurgency campaigns in the first decades of this century, which came to be labeled “endless wars,” were not remarkable for their speed. Washington’s military campaign in Afghanistan was the longest in US history and ultimately unsuccessful: despite being driven out at the start of the US invasion, the Taliban eventually returned.

Nor is this problem limited to the United States and its allies. In February 2022, Russia launched a large-scale invasion of Ukraine, which was supposed to overrun the country in a matter of days. Now, even if a ceasefire can be reached, the war will have lasted more than three years, during which time it has been dominated by fierce fighting and attrition rather than bold and daring actions. Similarly, when Israel launched its invasion of Gaza in retaliation for Hamas’s assault and hostage-taking on October 7, 2023, US President Joe Biden called for the Israeli operation to be “swift, decisive, and overwhelming.” Instead, it continued for 15 months, spreading to other fronts in Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen, before a fragile ceasefire was reached in January 2025. By mid-March, the war had reignited. And that leaves aside numerous conflicts in Africa, including Sudan and the Sahel, with no end in sight.

The idea that surprise offensives could produce decisive victories began to be incorporated into military thinking in the 19th century. But time and again, the forces undertaking them have shown how difficult it is to bring a war to an early and satisfactory conclusion. European military leaders were confident that the war that began in the summer of 1914 could be “over by Christmas” — a phrase that is still invoked whenever generals seem overly optimistic; instead, the fighting lasted until November 1918, ending with rapid offensives, but only after years of devastating war in trenches along nearly static front lines.

In 1940, Germany conquered much of Western Europe in a matter of weeks through a blitzkrieg, bringing together armored and air forces. But it was unable to finish the job and, after initial rapid advances against the Soviet Union in 1941, was drawn into a brutal war with enormous losses on both sides, which ended only nearly four years later with the total collapse of the Third Reich. Similarly, the Japanese military leadership’s decision to launch a surprise attack on the United States in December 1941 ended in the catastrophic defeat of the Japanese empire in August 1945. In both world wars, the key to victory was not so much military skill as unbeatable resilience.

However, despite this long history of protracted conflicts, military strategists continue to shape their thinking around short wars, in which everything should be decided in the first days, or even hours, of combat. According to this model, strategies can be devised that will catch the enemy off guard with the speed, direction, and ferocity of the initial attack. With the constant possibility of the United States being drawn into a war with China over Taiwan, the viability of such strategies has become a pressing issue: can China quickly conquer the island using lightning force, or will Taiwan, backed by the United States, be able to stop such an attack?

What is clear is that, against a backdrop of growing tensions between the United States and a variety of antagonists, there is a critical misalignment in defense planning. Recognizing the tendency of wars to become protracted, some strategists have begun to warn of the dangers of falling into the “short war” trap. By focusing on short wars, strategists rely too heavily on initial battle plans that may not play out in practice—with bitter consequences. Andrew Krepinevich argued that a protracted US war with China would “involve types of warfare with which the belligerents have little experience” and could represent “the decisive military test of our time.” Moreover, failure to prepare for long wars creates vulnerabilities of its own. To transition from short to long wars, countries must place different demands on their military and society as a whole. They will also need to reevaluate their objectives and what they are prepared to commit to achieve them.

Once military planners accept that any major contemporary war may not end quickly, they are required to adopt a different mindset. Short wars are fought with whatever resources are available at the time; long wars require the development of capabilities that are geared toward changing operational imperatives, as demonstrated by the ongoing transformation of drone warfare in Ukraine. Short wars may only cause temporary disruptions to a country’s economy and society and do not require extensive supply lines; long wars require strategies for maintaining popular support, functioning economies, and secure means of rearming, resupplying, and refueling troops. Long wars also require constant adaptation and evolution: the longer a conflict lasts, the greater the pressure for innovations in tactics and technology that could lead to progress. Even for a great power, failure to prepare and then rise to meet these challenges could be disastrous.

However, it is also fair to ask how realistic it is to plan wars that have no clear end. It is one thing to sustain a prolonged counterinsurgency campaign, but quite another to prepare for a conflict that would involve continuous and substantial losses of life, equipment, and ammunition over a long period of time. For defense strategists, there may also be significant obstacles to this type of planning: the armies they serve may not have the resources necessary to prepare for a long war. The answer to this dilemma is not to prepare for wars of indeterminate duration, but to develop theories of victory that are realistic in their political objectives and flexible in how they might be achieved.

The error of short wars

The advantages of short wars—immediate success at a tolerable cost—are so obvious that it is difficult to argue for knowingly engaging in a long one. On the other hand, even admitting the possibility that a war might become protracted can seem to betray doubts about the ability of one’s military to triumph over an adversary. If strategists have little or no confidence that a potential war can be short, then the only prudent policy is not to wage it at all. However, for a country such as the United States, it may not be possible to rule out conflict with another similar great power, even if rapid victory is not assured. Although Western leaders have an understandable aversion to intervention in civil wars, it is also possible that the actions of a non-state adversary could become so persistent and damaging that direct action to counter the threat becomes imperative, regardless of how long it might take.

This is why military strategists continue to model their plans around short wars, even when a protracted conflict cannot be ruled out. During the Cold War, the main reason why the two sides did not allocate large resources to prepare for a long war was the assumption that nuclear weapons would be used sooner rather than later. In the current era, this threat remains. But the prospect of a conflict between major powers turning into something like the cataclysmic world wars of the last century is frightening—adding urgency to plans designed to produce a quick victory with conventional forces.

Strategies for conducting this ideal type of war are geared primarily toward moving quickly, with an element of surprise and with sufficient force to overwhelm enemies before they can mount an adequate response. New combat technologies tend to be evaluated based on how much they could help achieve rapid success on the battlefield, rather than how well they could help ensure lasting peace. Take artificial intelligence, for example. By leveraging artificial intelligence, armies will be able to assess situations on the battlefield, identify options, and then select and implement those options in a matter of seconds. Vital decisions could soon be made so quickly that those in command, let alone the enemy, will barely appreciate what is happening.

So ingrained is the fixation on speed that generations of American military commanders have learned to tremble at the mention of attraction warfare, embracing decisive maneuver as the path to quick victories. Long battles like those now taking place in Ukraine—where both sides are trying to degrade each other’s capabilities, and progress is measured by the number of bodies, destroyed equipment, and depleted ammunition stocks—are not only discouraging for the belligerent countries, but also extremely time-consuming and costly. In Ukraine, both sides have already spent extraordinary resources, and neither is close to anything resembling victory. Not all wars are fought with the same intensity as the Russian-Ukrainian war, but even prolonged irregular warfare can have a severe impact, resulting in a growing sense of futility, in addition to rising costs.

Although it is well known that bold surprise attacks often deliver much less than they promise and that it is much easier to start wars than to end them, strategists still fear that potential enemies may be more confident in their plans for a quick victory and will act accordingly. This means they are required to focus on the likely opening phase of the war. It can be assumed, for example, that China has a strategy for conquering Taiwan that aims to catch the United States off guard, leaving Washington to respond in ways that either have no hope of success or are likely to make matters worse.

To anticipate such a surprise attack, US strategists have devoted considerable time to assessing how the United States and other allies can help Taiwan counter China’s opening moves—as Ukraine did with Russia in February 2022—and then make it difficult for China to sustain a complex operation at some distance from the mainland. But even this scenario could easily lead to retreat: if the initial countermeasures by Taiwanese forces and their Western allies are successful and China gets bogged down but does not retreat, Taiwan and the United States would still face the problem of dealing with a situation in which Chinese forces are present on the island. As Ukraine has learned, it is possible to become bogged down in a protracted war because an imprudent adversary miscalculated the risks.

That is not to say that modern armed conflicts never end in quick victories. In June 1967, it took Israel less than a week to decisively defeat a coalition of Arab states in the Six-Day War; three years later, when India intervened in the Bangladesh War of Independence, Indian forces needed only 13 days to defeat Pakistan. Britain’s 1982 victory over Argentina in the Falklands War was fairly quick. But since the end of the Cold War, there have been many more wars in which early successes faltered, lost momentum, or failed to achieve enough, turning conflicts into something much more difficult to resolve.

Indeed, for some types of belligerents, the pervasive problem of long wars can offer an important advantage. Insurgency fighters, terrorists, rebels, and secessionists can engage in their campaigns knowing that it will take time to undermine established power structures and assuming that they will simply outlast their more powerful enemies. A group that knows it is unlikely to triumph in a quick confrontation may recognize that it has a better chance of success in a long and difficult struggle, as the enemy becomes exhausted and loses morale. Thus, in the last century, anti-colonial movements and, more recently, jihadist groups have engaged in decades-long wars not because of a poor strategy, but because they had no other option. Especially when faced with military intervention by a powerful foreign army, the best option for such organizations is often to let the enemy tire itself out in an inconclusive struggle and then return at the right moment, as the Taliban did in Afghanistan.

In contrast, major powers tend to assume that their significant military superiority will quickly overwhelm their adversaries. This overconfidence means that they fail to appreciate the limits of military power and thus set goals that can be achieved, if at all, only through protracted struggle. A bigger problem is that by focusing on immediate results on the battlefield, they may neglect the broader elements necessary for success, such as securing the conditions for a lasting peace or effectively managing an occupied country where a hostile regime has been overthrown but a legitimate government has not yet been installed. In practice, therefore, the challenge is not simply to plan long wars rather than short ones, but to plan wars that have a workable theory of victory with realistic objectives, however long it takes to achieve them.

Not losing means winning

Effective combat strategy is a matter not only of military method but also of political purpose. Obviously, military moves are more successful when combined with limited political ambition. The 1991 Gulf War succeeded because the George H. W. Bush administration Bush administration sought only to expel Iraq from Kuwait and not to overthrow Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 might have been more successful if it had focused on Donbas rather than trying to take political control of the entire country.

With limited ambition, it is also easier to compromise. A workable theory of victory requires a strategy in which military and political objectives are aligned. It may be that the only way to resolve a dispute is through the total defeat of the enemy, in which case sufficient resources must be allocated to the task. At other times, a military initiative may be taken in the firm expectation that it will lead to early negotiations. This was Argentina’s view in April 1982 when it occupied the Falkland Islands. When Egyptian President Anwar al-Sadat ordered his armed forces to cross the Suez Canal in October 1973, he did so to create the conditions for direct talks with Israel. His armed forces were pushed back, but he achieved his political goal.

Underestimating the political and military resources of the enemy is one of the main reasons why short war strategies fail. Argentina assumed that the United Kingdom would accept a fait accompli when it conquered the Falklands and did not imagine that the British would send an operational force to liberate the islands. Wars are often launched in the mistaken belief that the population of the opposing power will soon yield under attack. Invaders may assume that part of the population will embrace them, as was seen in the 1980 invasion of Iran by Iraq and, indeed, in Iran’s counter-invasion of Iraq. Russia based its large-scale attack on Ukraine on a similar misinterpretation: it assumed that there was a besieged minority—in this case, Russian speakers—that would welcome its forces; that the government in Kyiv lacked legitimacy and could be easily overthrown; and that Western promises of support for Ukraine would not mean much. None of these assumptions survived the first days of the war.

When a short war plan does not produce the anticipated victory, the challenge for military leaders is to realign means and ends. By September 2022, President Vladimir Putin realized that Russia risked a humiliating defeat if it could not bring more troops to the front and put its economy on a comprehensive war footing. As the leader of an authoritarian state, Putin could stifle internal opposition and maintain control over the media, and he did not have to worry too much about public opinion. However, he needed a new narrative. Having claimed before the war that Ukraine was not a real country and that its “neo-Nazi” leaders had seized power in a coup in 2014, he could not explain why the country had failed to collapse when hit by superior Russian force. So Putin changed his story: Ukraine, he claimed, was being used by NATO countries, particularly the United States and Britain, to pursue their own Russophobic goals.

Despite initially presenting the invasion as a limited “special military operation,” the Kremlin now portrayed it as an existential struggle. This meant that instead of simply stopping Ukraine from being so problematic, Russia was now trying to prove to NATO countries that it could not be broken by economic sanctions or the alliance’s arms deliveries to Ukraine. By describing the war as defensive, the Russian government was telling its people how much was at stake, while warning them that they could not expect a quick victory. Instead of scaling back its objectives to acknowledge the difficulties of defeating the Ukrainians in battle, the Kremlin has expanded them to justify the extra effort. By annexing four Ukrainian provinces in addition to Crimea and continuing to demand a supine government in Kyiv, Russia has made the war harder, not easier, to end. This situation illustrates the difficulty of ending wars that are not going well: the possibility of failure often adds a political objective—the desire to avoid appearing weak and incompetent. Concerns about reputation were one of the reasons the US government remained in Vietnam long after it was clear that victory was not within reach.

Replacing a failed theory of victory with a more promising one requires not only reassessing the enemy’s real strengths, but also acknowledging the flaws in the political assumptions underlying the moves toward engagement. Suppose that US President Donald Trump’s push for a ceasefire bears fruit, leaving the war frozen along the current front lines. Moscow could present its territorial gains as a kind of success, but it could not truly claim victory as long as Ukraine has a functioning independent and pro-Western government. If Ukraine were to temporarily accept its territorial losses but still be able to build up its forces and obtain some form of security guarantees with the help of its Western partners, the outcome would still be far from Russia’s often-stated demand for a neutral, demilitarized Ukraine. Russia would be left to administer and subsidize devastated territories with a resentful population, while having to defend long ceasefire lines.

However, although Russia has failed to win the war, it has not lost it so far. It was forced to withdraw from some territories conquered at the beginning of the war, but since the end of 2023 it has made slow but steady gains in the east. On the other hand, Ukraine has not lost, as it has successfully resisted Russian attempts at subjugation and forced Russia to pay a heavy price for every square mile gained. Most importantly, it remains a functioning state.

No end in sight

In commentary on contemporary warfare, the distinction between “winning” and “not losing” is vital but difficult to grasp. The difference is not intuitive because of the assumption that there will always be a winner in war and because, at any given moment, one side may appear to be winning even if it has not actually won. The situation of “not losing” is not really captured by terms such as stalemate and deadlock, as these imply little military movement. Both sides can “not lose” when neither can impose victory on the other, even if one or both are occasionally able to improve their positions. This is why proposals to end protracted wars normally take the form of calls for ceasefires.

The problem with ceasefires, however, is that the parties involved in the conflict tend to view them as merely pauses in the fighting. They can have little effect on the underlying disputes and may simply give both sides a chance to recover and regroup for the next round. The ceasefire that ended the Korean War in 1953 has lasted for over 70 years, but the conflict remains unresolved and both sides continue to prepare for future war.

Most models of war continue to assume the interaction of two regular armed forces. According to this framework, a decisive military victory comes when the enemy forces can no longer function, and such an outcome should also translate into a political victory, as the defeated side has no choice but to accept the victor’s terms. After years of tension and intermittent fighting, one side may reach a position where it can claim an unequivocal victory. One example is Azerbaijan’s offensive in Nagorno-Karabakh in 2023, which could end a three-decade war with Armenia.

Alternatively, even if a country’s armed forces are still largely intact, pressure may build on its government to find a way out of the conflict because of the cumulative human and economic costs. Or there may be no prospect of real victory, as Serbia came to recognize in its war against NATO in Kosovo in 1999. When one of the parties involved in a conflict experiences regime change at home, this can also lead to a sudden end to hostilities. When they end, long wars leave behind bitter and lasting legacies.

Even in cases where a political settlement, rather than just a ceasefire, can be reached, a conflict may not be resolved. Territorial adjustments and probably substantial economic and political concessions by the defeated party can produce resentment and a desire for redress among the defeated population. A defeated country may remain determined to find ways to recover what it has lost. This was France’s position after it lost Alsace-Lorraine to Germany in 1871 after the Franco-Prussian War. In the Falklands War, Argentina claimed to be recovering territory it had lost a century and a half earlier. Moreover, for the victor, the enemy territory that has been conquered and annexed will have to be governed and supervised. If the population cannot be subjugated, what may initially appear to be a successful land grab can lead to a volatile situation of terrorism and insurgency.

Unlike standard models of war, in which hostilities usually have a clear starting point and an equally clear end date, contemporary conflicts often have blurred boundaries. They tend to go through stages, which may include war and periods of relative calm. Take the United States’ conflict with Iraq. In 1991, Iraqi forces were quickly defeated by a US-led coalition in what appeared to be a short and decisive war. But because the United States decided not to occupy the country, the war left Saddam in power, and his continued defiance created a sense of unfinished business. In 2003, under President George W. Bush, the United States invaded Iraq again and achieved another quick victory, and this time Saddam’s Baathist dictatorship was overthrown. But the process of replacing it with something new precipitated years of devastating intercommunal violence that at times came close to full-scale civil war. Some of this instability continues to this day.

Because civil wars and counterinsurgency operations are fought within and between populations, civilians are the ones most affected by these wars, not only through deliberate sectarian violence or crossfire, but also because they are forced to flee their homes. This is one reason why these wars tend to lead to protracted conflict and chaos. Even when an intervening power decides to leave, as both the Soviet Union and the US-led coalition did in Afghanistan, that does not mean the conflict ends—only that it takes new forms.

In 2001, the United States had a clear “short war” plan for overthrowing the Taliban, which it implemented successfully and relatively efficiently using regular forces combined with the Afghan-led Northern Alliance. But there was no clear strategy for the next stage. The problems Washington faced were not caused by a stubborn opponent fighting with regular forces, but by endemic violence, in which threats were irregular and emerged from civil society, and in which any satisfactory outcome depended on the elusive goals of bringing decent governance and security to the population. Without external forces to prop up the government, the Taliban was able to return, and the history of the conflict in Afghanistan continued.

Israel’s triumph in 1967—a paradigmatic case of quick victory—left it occupying a large territory with resentful populations. It created the conditions for many wars that followed, including the Middle East wars that erupted with the Hamas attacks of October 7, 2023. Since then, Israel has waged campaigns against the group in the Gaza Strip, from which Israel withdrew in 2005, and against Hezbollah in Lebanon, where Israel fought a poorly managed operation in 1982. The two campaigns took similar forms, combining ground operations to destroy enemy facilities, including tunnel networks, with strikes against weapons stockpiles, rocket launchers, and enemy commanders.

Both conflicts caused huge civilian casualties and widespread destruction of civilian areas and infrastructure. However, Lebanon could be considered a success because Hezbollah agreed to a ceasefire while the war in Gaza was still ongoing, something it had said it would refuse to do. In contrast, the short-lived ceasefire in Gaza was not a victory, as the Israeli government had set the goal of completely eliminating Hamas, which it did not achieve. In March, after a break in negotiations, Israel resumed the war, still without a clear strategy to end the conflict definitively. Although severely depleted, Hamas continues to function and, without an agreed plan for the future governance of the Gaza Strip or a viable Palestinian alternative, will remain an influential movement.

In Africa, protracted conflicts seem endemic. Here, the best predictor of future violence is past violence. Across the continent, civil wars flare up and then subside. These often reflect deep ethnic and social divisions, exacerbated by external intervention, as well as more brutal forms of power struggle. The underlying instability ensures constant conflict in which individuals and groups can stake a claim, perhaps because fighting provides both an incentive and a cover for trafficking in arms, people, and illicit goods. The current war in Sudan involves civil conflicts and shifting loyalties, in which an oppressive regime was overthrown by a coalition, which then turned on itself, leading to an even more vicious war. It also involves external actors, such as Egypt and the United Arab Emirates, who are more concerned with preventing their opponents from gaining an advantage than with ending the violence and creating the conditions for recovery and reconstruction.

As a rule, ceasefires and peace treaties, when they happen, often don’t last long. Sudanese parties have signed over 46 peace treaties since the country gained independence in 1956. Wars tend to be identified when they turn into direct military confrontation, but the pre- and post-war turmoil is part of the same process. Rather than discrete events with a beginning, middle, and end, wars may be better understood as the result of weak and dysfunctional political relationships that are difficult to manage through nonviolent means.

Another type of deterrence

The main lesson that the United States and its allies can draw from their considerable experience of long wars is that it is better to avoid them. If the United States becomes involved in a protracted conflict between major powers, the entire economy and society of the country will have to be put on a war footing. Even if such a war ended in something close to victory, the population would probably be shattered and the state would be drained of all its reserve capacity. Moreover, given the intensity of contemporary warfare, the rate of wear and tear, and the costs of modern weaponry, increased investment in new equipment and ammunition might still be insufficient to sustain a future war for very long. At a minimum, the United States and its partners should procure sufficient stocks in advance to remain in the fight long enough to set in motion a much more drastic, large-scale mobilization.

And then, of course, there is the risk of nuclear war. At some point during a protracted war involving either Russia or China, the temptation to use nuclear weapons could prove irresistible. Such a scenario would probably lead to an abrupt end to a long conventional war. After seven decades of debate about nuclear strategy, no credible theory of nuclear victory over an adversary capable of retaliating in kind has yet been found. As with conventional war strategists, nuclear planners have focused on speed and have brilliantly executed opening moves aimed at eliminating the enemy’s means of retaliation and removing its leadership, or at least alarming and confusing it to generate paralysis of indecision.

All these theories, however, seemed uncertain and speculative, since any first strike would have to face the risk of an enemy launch in warning, as well as enough surviving systems for a devastating retaliation. Fortunately, these theories have never been tested in practice. A nuclear offensive that does not produce an immediate victory and instead results in multiple nuclear exchanges might not be prolonged, but it would undoubtedly be grim. This is why the condition has been described as one of “mutually assured destruction.”

It is worth remembering that one of the reasons why the US defense establishment embraced the nuclear age with such enthusiasm was that it offered an alternative to the devastating world wars of the early 20th century. Strategists were already aware that all-out battles between major powers could be exceptionally long, bloody, and costly. As with nuclear deterrence, the major powers may now need to prepare more visibly for longer conventional wars than current plans assume — if only to ensure that they do not happen. And, as the war in Ukraine has painfully demonstrated, great powers can be involved in long wars even when they are not directly engaged in combat. The United States and its allies will need to improve their defense industrial bases and build up stocks to better prepare for such situations in the future.

The conceptual challenge posed by this type of preparation, however, is different from what would be required to prepare for a titanic confrontation between superpowers. Although the prospect may be unpleasant, military planners need to think about managing a conflict that risks becoming protracted in the same way that they have thought about managing nuclear escalation. By preparing for protraction and reducing any potential aggressor’s confidence in its ability to wage a successful short war, defense strategists could offer another type of deterrence: they would warn adversaries that any victory, even if it could be achieved, would come at an unacceptably high cost to their military, economy, and society.