| About the Maritime Security Forum The Maritime Security Forum (MSF), the scientific structure of the Club of Admirals, is a platform for the creation and dissemination of knowledge and information in the field of maritime security, which carries out scientific work and organises events for public information and debate.The MSF is also a medium for dissemination and public communication in the fields of ship policy, shipping, safety, maritime security and defence. Maritime Security Forumwww.forumulsecuritatiimaritime.roContact: contact@forumulsecuritatiimaritime.ro |

Russia’s strategic naval collapse in the context of the war in Ukraine (2022-2025)

Authors:Admiral (rtr) PhD. Aurel POPA, President, Maritime Security Forum ; Rear Admiral Fl. (rtr) Lector. Univ. PhD. Sorin LEARSCHI, Director, Maritime Security Forum

“A nation that cannot defend its coasts is not a safe nation.”

Franklin D. Roosevelt – former US President

MARITIME SECURITY FORUM ,STUDY, APRIL 2025, Download in PDF format here

Contents

Russia’s strategic naval collapse in the context of the war in Ukraine (2022-2025) 1

- Abstract 4

- ARGUMENT.. 5

- Russia’s strategic naval collapse (2022-2025) in the context of the war in Ukraine. 8

- 1. Introduction. 8

- 2. Background and Russia’s naval capabilities before 2022. 9

- Initial strategic objectives (February 2022) 10

- Turkey’s position and the Mont Mont Convention reux. 11

- Initial naval capabilities. 11

- Vulnerability assessment 12

- 3. 2022 – From domination to the first naval defeats. 12

- Initial Russian offensive and control of the northern Black Sea. 12

- First Russian naval losses in 2022. 13

- Snake Island campaign and other blows (May-June 2022) 16

- 4. The year 2023 – Russia’s Black Sea Fleet in the Black Sea is in sharp decline. 19

- Russian consolidation and first drone strikes (January-June 2023) 19

- Major strikes against the Russian Fleet (August-September 2023) 21

- Impact on the fleet and situation at the end of 2023. 24

- 5. The year 2024 – Russian fleet in the Black Sea almost completely neutralised. 26

- Continuation of naval drone attacks (January – March 2024) 26

- ATACMS and Storm Shadow missile strikes (May – November 2024) 28

- 6. The situation in early 2025. 31

- 7. Impact on Russia’s strategic maritime projection and economic/logistical security. 32

- Diminishing Russia’s strategic maritime projection. 32

- Impact on Russia’s economic and logistical security. 34

- 8. The role of new technologies, precision weapons and Ukrainian tactics. 37

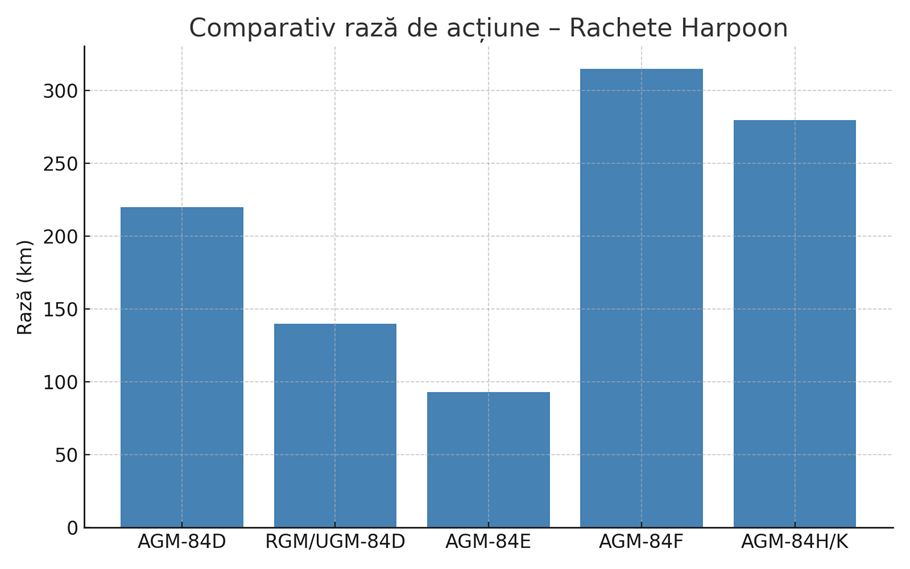

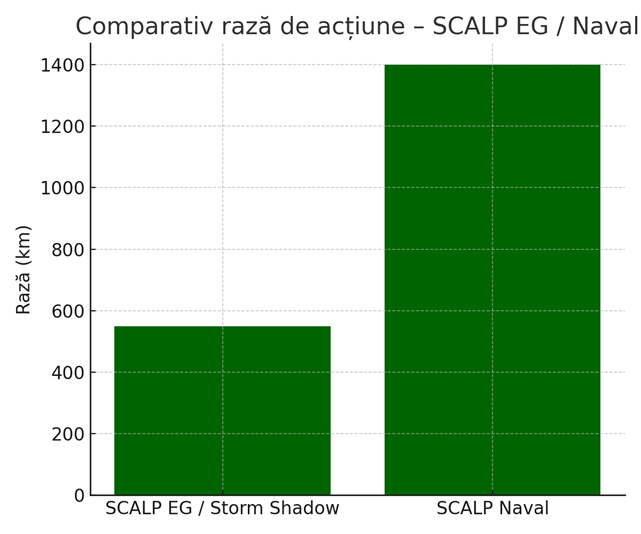

- Coastal anti-ship missiles and precision strikes. 37

- Aerial drones and asymmetric warfare. 39

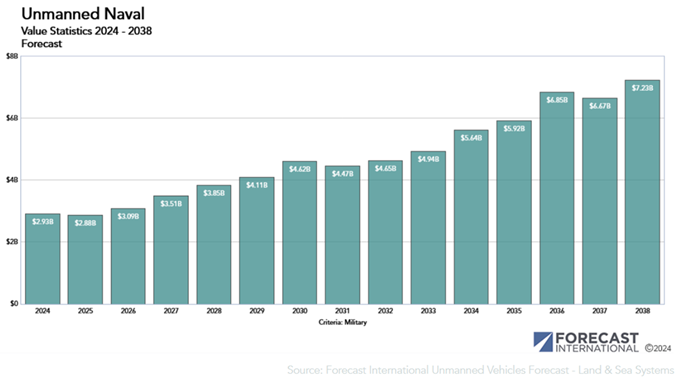

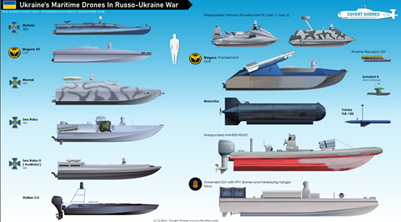

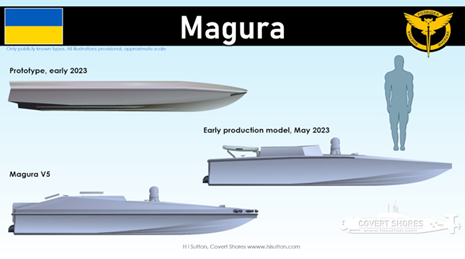

- Naval drones – a new era of war at sea. 40

- Ukrainian “hybrid warfare” tactics in the naval field. 43

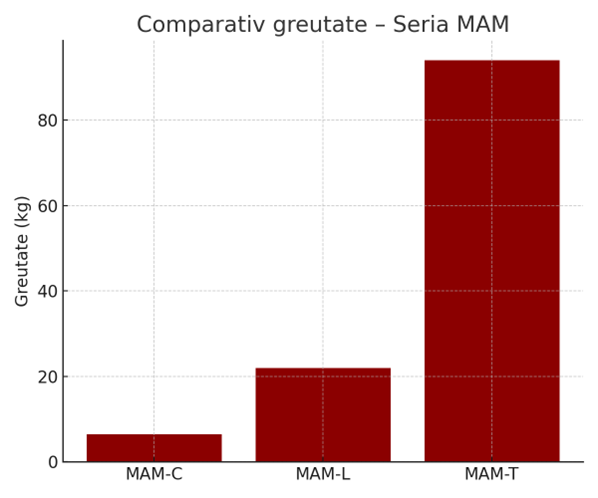

- Main characteristics of the weapon/means of striking. 45

- Sea mines. 52

- 9. Lessons learnt and implications for Russian and global naval doctrine. 54

- Using BT2 against Russian invasion in 2022. 54

- Tactical lessons from the use of Bayraktar TB2 drones in the Black Sea area. 56

- Further use and vulnerability. 56

- Lessons for Russian naval doctrine. 58

- Global lessons and international implications. 61

- 10. Lessons learned applicable to the Romanian Naval Forces: strategic perspectives and needs for modernisation and equipment 64

- Lessons learnt from the regional and allied context 65

- Operational lessons from the Black Sea theatre and implications for Romania. 65

- Purchase of modern multifunctional platforms. 65

- Final recommendations on the purchase of OPVs. 68

- Naval infrastructure and logistis. 69

- Key lessons from the conflict: 70

- Doctrinal and institutional recommendations. 71

- Recommendations trans regional 72

- Changing the model: from passive defence to active deterrence. The need to redefine the role of the Romanian Naval Forces in NATO’s maritime security architecture. 76

- The need to develop a National Strategy for Romania’s Maritime Security: between the imperatives of the geostrategic reality and the strategic obligation of the present 77

- 11. Final considerations: changing the naval warfare paradigm.. 78

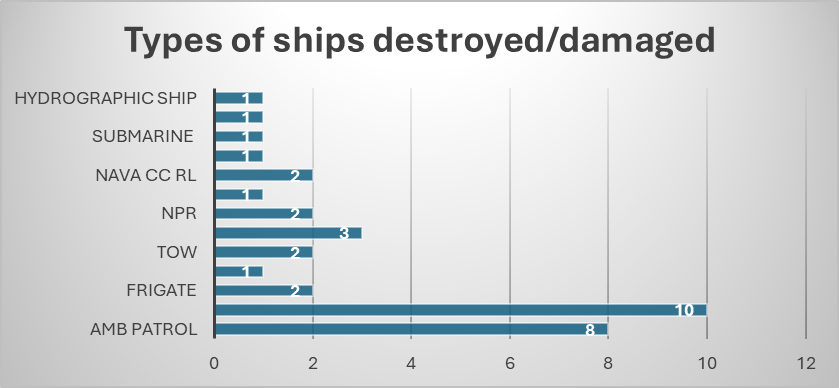

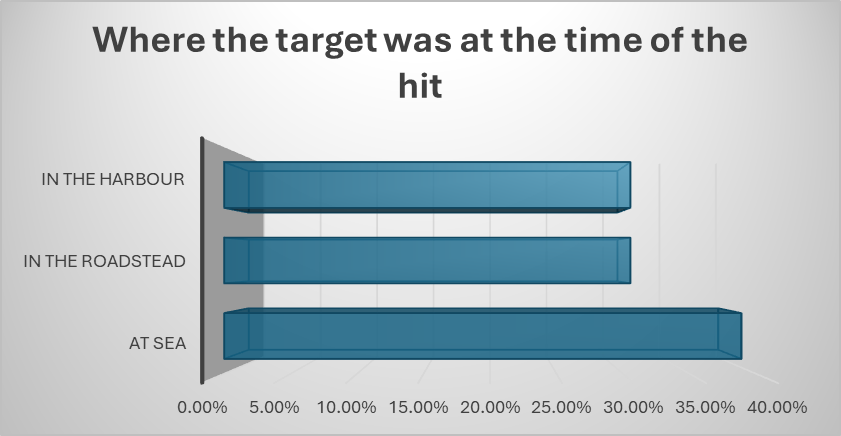

- ANNEX 1- Table with the results of the attacks on the Black Sea Fleet 81

- ANNEX 2-Maritime drones. 90

- BIBLIOGRAPHY.. 100

Abstract

The present study provides a structured and comprehensive analysis of one of the most unexpected and strategically significant phenomena of the Russian-Ukrainian war (2022-2025): the progressive collapse of the naval capabilities of the Russian Federation. Through a chronological and thematic approach, the research examines the operational losses suffered by the Russian Navy, especially in the Black Sea theatre, emphasising the profound implications of these losses for contemporary naval doctrines and regional security balances. Moving beyond the simple inventory of destroyed or neutralised military assets, the study explores the technological, tactical, and strategic mechanisms that led to the erosion of Russian maritime supremacy. Special attention is given to the impact of asymmetric warfare, the extensive use of unmanned systems, and the strategic innovation demonstrated by Ukraine. This research contributes to the literature on modern warfare by highlighting the transformation of maritime conflicts in the 21st century and the growing vulnerability of conventional naval forces when confronted with flexible, low-cost and adaptive strategies. The study’s conclusions invite a rethinking of the role of naval power in future conflicts, while offering analytical tools for the academic and strategic community concerned with security studies.

Keywords: Russian Navy; Black Sea; Naval Losses; Maritime Security; Asymmetric Warfare; Unmanned Systems; Ukraine Conflict

JEL Classification: F52 ,H56, N47

ARGUMENT

The analysis of contemporary conflicts, especially in their naval dimension, remains insufficiently covered in recent strategic literature, despite the marked developments in the instruments and technologies of sea combat. Our century, marked by the chameleon-like features of hybrid warfare and the intersection of the grey areas of confrontation with new combat technologies, has revealed a dynamic of naval conflicts that can no longer be understood solely in conventional terms of numerical or technological superiority.

Our study aims to provide those interested with an in-depth strategic analysis of one of the least anticipated and at the same time spectacular phenomena of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict: the accelerated degradation of the myth of the Russian Federation’s naval capabilities, especially in the Black Sea, as a result of Ukraine’s technological, tactical and informational adaptation.

Between 2022 and 2025, the war between Russia and Ukraine produced important transformations not only on land and in the air, but also in maritime space, demonstrating that traditional naval supremacy can be rapidly eroded by asymmetric, creative and relatively low-cost means. The Russian fleet, perceived for decades as an essential instrument of force projection in the Black Sea, became, in the course of the conflict, a vivid example of the vulnerability of conventional large structures to new types of warfare.

In what follows we have analysed in stages, the key moments, losses, adaptations and lessons resulting from this process of strategic naval collapse. Careful documentation, the use of international sources, the integration of quantitative data and comparative tables provide the reader with an x-ray of a military phenomenon unprecedented in recent history, together with an invitation to reflection on the future of naval doctrines, military technology and regional balances.

In this endeavour, we have embarked on an increasingly necessary line of research, namely the critical and analytical assessment of how traditional naval structures can become vulnerable to adaptive, asymmetric, creative strategies. In particular, the degradation of the Russian military fleet in the Ukraine conflict provides a case study of remarkable strategic value in terms of the magnitude and spectacular nature of the losses and, more importantly, the mechanisms and root causes that led to this seemingly implausible naval collapse in the context of the earlier perception of Russian maritime power.

The importance of this study does not derive solely from its descriptive or quantitative value, but from its commitment to understanding the naval phenomenon as an integral part of the profound transformations affecting military art and science in our age. The disappearance of certain ships, submarines or maritime infrastructures must be analysed both as a simple statistical reality and as a symptom of a crisis of adaptability, doctrinal rigidity and, often, an underestimation of the creative capacity of the adversary.

From this perspective, this paper opens a space for problematising how naval supremacy can become, in a relatively short period of time, a strategic vulnerability. The traditional tools of maritime force projection are today confronted with problems that come not only from the conventional military area, but also from the sphere of low-cost technologies, autonomous drones, precision munitions, dispersion and infiltration tactics. Alongside all this, the proposed analysis demonstrates how the maritime domain, once perceived as an environment of slow and predictable operations, is rapidly transforming into a theatre of operations characterised by speed, flexibility, information volatility and structural vulnerability. Russia’s naval losses in the war in Ukraine are thus not only a result of the actual fighting, but also a consequence of the unsuitability of a certain type of military thinking to the realities of modern warfare.

The relevance of this study for international research and for the security community is amplified by the fact that understanding the mechanisms of naval collapse is crucial for anticipating and preventing similar developments in other regional or global contexts. Modern fleets, however well-equipped in technical terms, are nonetheless taking into account the lessons learnt from this conflict. Researchers, strategists, security analysts and decision-makers need to rethink their grids for interpreting the naval and maritime-strategic reality.

In the end, this paper remains, of course, an exercise in applied research, but it also aspires to be a discreet invitation to a continuous re-examination of established models in military analysis. The realities of the present – often more complex and unpredictable than the established models – make it increasingly clear that a different interpretative framework is needed, through intellectual flexibility, methodological openness and the affirmation of technological, psychological and informational dimensions in the study of military phenomena.

Russia’s strategic naval collapse as a highly topical issue is perhaps the clearest warning of the beginning of the 21st century of the dangers of rigidity, of overestimating one’s own strength and underestimating the innovative potential of the adversary. This paper does not propose simple formulas, but provides tools for understanding, analysing and reflecting – all the more necessary in a strategic order marked by uncertainty, ruptures and profound redefinitions.

The sources for this study are varied:

- Ukrainian media reports and official Ukrainian announcements documenting Russian losses (e.g. Oryx visually confirmed over 17 Russian ships destroyed/damaged[1] , including Moskva).

- Analyses by military experts (War on the Rocks[2] , Wilson Centre[3] etc.) which contextualised the events.

- Communications from the UK Ministry of Defence and NATO officials, which provided quantitative (20% of the fleet destroyed in 4 months[4] and qualitative assessments of the impact.

- Investigative media reports (Mediazona, Meduza) and OSINT sources for details of casualties and condition of ships.

- Comments by former officers (such as Admiral Pascal Ausseur)[5] providing doctrinal perspective.

- Historical databases (list of naval losses on Wikipedia[6] or compiled by Oryx) to quantify material losses.

- These sources confirm the facts and support our conclusions:

- The Russian fleet has lost at least 11 large ships (including a cruiser, a submarine, several destroyers and corvettes), plus numerous smaller ones.

- Russia has indirectly recognised the problems, moving the fleet and publicly admitted through proxy sources the humiliating losses (AFP via Agerpres wrote about “heavy military losses in the Black Sea”[7] ).

- Ukrainian drones and Western missiles were decisive factors, forcing Russia to “move its ships … away from Sevastopol” to protect them[8] and allowing Ukraine to “force an end to the blockade”.

Authors

Bucharest, April 2025

Russia’s strategic naval collapse (2022-2025) in the context of the war in Ukraine

“Sea power is essential to any nation

that wants to protect its interests and assert its influence.”

Alfred Thayer Mahan – American naval theorist

1. Introduction

The war that Russia launched against Ukraine in 2022 was initially seen almost exclusively through the prism of land and air battles. However, the conflict also had an important maritime dimension, often neglected in early accounts. The Russian Navy – considered on paper to be the second most powerful in the world thanks to its fleet of nuclear submarines[9] – concentrated a significant part of its effort in the Black Sea area, aiming to dominate the Ukrainian coastline, blockade harbours and support the land invasion. From the very first days of the conflict, the Russian fleet imposed a naval blockade of Ukraine and threatened amphibious landings near Odessa. But during 2022-2025, this apparent Russian naval superiority eroded dramatically. Ukraine – although left almost without a military fleet after its losses in 2014 – has managed, through means of strategic optimisation and modern weaponry, to bring about the strategic collapse of Russian naval power in the Black Sea.

The aim of this study is to analyse in depth the degradation of Russia’s maritime capabilities in the period 2022-2025, highlighting in particular the collapse of the Russian Black Sea Fleet and its implications. We will examine, chronologically and thematically, the naval losses suffered by Russia in each year, the factors that led to them, and the impact on Russia’s strategic maritime projection and its economic and logistical security. Particular emphasis will be placed on the role of new Ukrainian technologies and tactics – from precision anti-ship missiles to naval drones – in undermining the Russian fleet. We will also discuss lessons learnt and how these events are influencing Russian naval doctrine and global strategic thinking on war at sea.

Methodologically, the study is based on academic sources, military analyses and reliable media reports, duly cited. Information has been corroborated from Western sources (reports of strategic studies institutes, military intelligence bulletins), official Ukrainian sources, etc., as well as available Russian sources (although the latter tend to minimise or misrepresent losses). The structure of the paper is that of an academic analysis, with chapters devoted to each year (2022, 2023, 2024, 2025 situation respectively), followed by thematic chapters on strategic impact, the role of technology and doctrinal conclusions.

In what follows, we will begin by summarising the initial state of the Russian naval forces and Moscow’s naval objectives relative to the starting point of the conflict, in order to understand the magnitude of the subsequent decline. We will then detail, year by year, the progressive loss of maritime supremacy, listing the ships destroyed or damaged (both in the Black Sea Fleet and – to the extent of involvement – in the Northern, Pacific and Baltic fleets). We go on to analyse how these losses have affected Russia’s ability to project power at sea and to protect its economic interests (such as export routes through the Black Sea). We will also examine Ukraine’s tactical innovations – from coastal missile strikes to unmanned naval vehicle attacks – that have changed the rules of the naval game. Finally, we focus on lessons learnt: what this failed naval campaign means for Russian naval doctrine, and what implications it has more broadly for modern naval warfare.

2. Background and Russia’s naval capabilities before 2022

Figure no. 1 Black Sea

At the beginning of 2022, the Russian Navy was still perceived as an advanced force, albeit with certain structural vulnerabilities. Russia had four main fleets – the Northern Fleet (the most powerful, including most strategic nuclear submarines), the Pacific Fleet, the Baltic Fleet and the Black Sea Fleet – plus the Caspian Fleet. Of these, the Black Sea Fleet has occupied a key place in Ukraine-related plans, with its main base in Sevastopol (Crimea) and controlling access to the Sea of Azov. After the annexation of Crimea in 2014, Moscow gradually strengthened this fleet, adding new vessels such as Admiral Grigorovich-class cruise missile-carrying frigates and upgraded Kilo-class diesel-electric submarines equipped with Kalibr missiles. The Black Sea Fleet also had its flagship flagship – the large missile cruiser Moskva – as well as modern missile-carrying corvettes and amphibious landing ships.

Initial strategic objectives (February 2022)

At the outbreak of the invasion on 24 February 2022, Russia used the Black Sea Fleet to gain immediate maritime superiority in the north-western Black Sea. In the early days Russian ships set up a blockade of Ukrainian ports[10] , paralysing Ukraine’s maritime exports. At the same time, the Russians strategically occupied the Serpents’ Island (45 km off the Romanian coast, controlling the mouth of the Danube) and threatened an amphibious landing in the Odessa area, forcing Ukraine to maintain troops in coastal defences. The importance of Snakes Island and the reason for the Russian assault also lay in the “desire to establish a land bridge to Crimea”[11] , reducing the vulnerability of the naval base at Sevastopol.

Figure 2 shows the Island of the Snakes

In parallel, Russia deployed a number of large landing ships from the Northern and Baltic Fleets to the Black Sea (passing through the straits before Turkey closed them) to support possible amphibious operations before the invasion. The Black Sea Fleet was joined by units from the Caspian Fleet, which sailed inland waterways and reached the Black Sea in small artillery ships.

Turkey’s position and the Mont Mont Convention reux

February 2022, was the month in which Turkey – a riparian country and custodian of access to the Black Sea under the Montreux Convention (1936) – decided to close the Bosphorus and Dardanelles Straits to all military vessels of the belligerents[12] . Under the convention, Turkey has the right to restrict passage in wartime if threatened or to limit conflict. The decision meant that Russia could not bring in naval reinforcements from outside the Black Sea (ships from the Northern, Baltic or Pacific Fleet could no longer enter), nor could the Russian Black Sea Fleet go out to operate in the Mediterranean. The only exception allowed by Montreux was for ships to return to their permanent base, which in practice meant that some Russian ships in the Mediterranean at the start of the war were stuck outside the Black Sea. Overall, Turkey’s decision prevented Russia from compensating for possible losses in the Black Sea with ships from other theatres of naval operations.

Initial naval capabilities

At the start of the invasion, the Black Sea Fleet included, among others:

- 1 Missile Carrier Cruiser, project 1164 Slava, flagship capable of supporting long-range anti-air defence of naval groups.

- 3 modern frigates, the Project 11356R Admiral Grigorovich – Admiral Makarov, Admiral Essen and Admiral Grigorovich (the last possible ???? deployed in the Mediterranean at the time) carrying Kalibr cruise missiles with which Russia often struck land targets deep in Ukraine.

- Missile-carrying corvettes and small Buyan-M (with Kalibr missiles) and Tarantan/Molnia (with older anti-ship missiles), plus light anti-submarine patrol vessels.

- Diesel-electric submarines (upgraded Kilo-class): 6 units deployed in Crimea, equipped with Kalibr missiles that can be launched from underwater, making them a formidable asset for Russia’s long-range strikes.

- Large (3 Ropucha-class and 1 Tapir-class) and medium-sized amphibious landing ships (Serna-class), theoretically prepared for landing in force.

- Other support vessels including mine dredgers, tugs, oil tankers, etc.

In the other fleets, Russia also possessed considerable capabilities (e.g. similar Moskva cruisers in the Northern and Pacific Fleet, destroyers, the aircraft carrier Admiral Kuznetsov – but under prolonged repair, etc.), but these forces could not intervene directly in the Black Sea because of the blockade of the straits. Therefore, the fate of the Russian naval campaign in Ukraine depended almost exclusively on the Black Sea Fleet and the units brought in before the invasion.

Although imposing on paper, the Russian Black Sea fleet had several vulnerabilities: many ships were of old Soviet design (the cruiser Moskva dates from the 1980s, as do the large landing ships), and their air and missile defence systems, while theoretically powerful, had not been tested in a high-intensity conflict. The relatively small area of the Black Sea and the proximity of enemy coasts (Ukraine, but also NATO – Romania, Bulgaria and Turkey) meant that Russian ships were exposed to early detection and attack from shore. A former French admiral remarked: “The Black Sea is a small sea” – the density of surveillance and ground attack means that no ship (Russian or Ukrainian) can operate undetected; any ship detected can be tracked and targeted. These geographic and technological aspects, dramatically combined, were to prove decisive in the evolution of naval warfare.

Thus, in early 2022 Russia set out with the ambition of a quick naval victory: to dominate the Black Sea, isolate Ukraine from access to the sea, and possibly carry out a strategic breakthrough. The following chapters will show how, contrary to these expectations, the Russian fleet was gradually pushed on the defensive and severely eroded as Ukraine fought back with ingenious and effective means.

Next, we analyse the years 2022, 2023 and 2024 in turn to highlight the progressive degradation of Russian maritime capabilities and the key moments that marked Russia’s strategic naval collapse in this conflict.

3. 2022 – From domination to the first naval defeats

Initial Russian offensive and control of the northern Black Sea

In the early weeks of the invasion (February-March 2022), Russia seemed to be achieving its immediate naval objectives. The Russian fleet was patrolling aggressively between Crimea and the Ukrainian coast, imposing a no-go zone for commercial shipping in much of the northern Black Sea[13] . Ukraine’s Black Sea ports (Odessa, Mykolaiv, Chornomorsk, etc.) have been blockaded, with dozens of foreign ships trapped. In the early days of the conflict, several neutral merchant ships were hit by missiles or floating mines, illustrating the danger in the conflict zone. One notable incident was on 3 March 2022, when the Panamanian-flagged cargo ship MV Helt[14] hit a drifting mine off Odessa and sank after allegedly being forced by the Russians to sail into a mined area. The presence of sea mines – detached from anchors or deliberately placed – became a high-grade risk at the start of the war, with NATO[15] and IMO[16] issuing navigational warnings.

The Russians managed to occupy Snake Island as early as 24 February, capturing the small Ukrainian garrison there (the famous “Russian ship, go…!” incident, when the border guards said to the cruiser Moskva). Control of the island has allowed the Russians to extend radar surveillance and ban sailing off Ukraine’s southern coast. At the same time, in late February and early March, several Ukrainian patrol vessels, tugs and Coast Guard boats were captured or sunk by Russian forces. Ukraine’s much weaker navy even sank its own flagship – the frigate Hetman Sahaidachnyi[17] – in Mykolaiv harbour on 3 March to prevent it falling into Russian hands. Virtually after the first few days, Ukraine was left without an operational surface fleet and Russia seemed free to dominate the sea.

Russian warships directly supported the land offensive in the south: they launched Kalibr cruise missiles from the sea against targets in Ukraine and carried out coastal bombardments. The Russian fleet also began to bring supplies and reinforcements by sea for the invading troops to the ports conquered by the Russians (Berdiansk, Mariupol, Henicesk on the Azov coast). The prospects of an amphibious landing near Odessa were being taken seriously; a group of Russian troopships (including those brought in from other fleets) swarmed close to the coast, putting pressure on Ukraine to disperse its defences.

As early as March 2022, however, the first signs that Russian naval supremacy would be challenged emerged. Ukraine retaliated by asymmetric means, capitalising on the aforementioned vulnerabilities. Below we will detail the loss of Russian ships in 2022, events that marked the beginning of the strategic decline of the Russian fleet.

First Russian naval losses in 2022

Berdiansk attack (24 March 2022)

An early blow for the Russian Navy came just a month after the invasion. On 24 March, Ukrainian forces attacked the port of Berdiansk (in the south of Zaporizhevsk Oblast, on the Azov Sea coast), where Russian landing ships had docked to unload equipment. Around 7am, loud explosions rocked the docks. The large landing ship Saratov (Tapir/Alligator class) was hit and destroyed at the quay[18] , subsequent fires led to the explosion of ammunition on board. Film footage showed the Saratov in flames, and two Ropucha-class dropships – Caesar Kunikov and Novocearkassk, alongside – rushed away, billowing smoke. According to Ukrainian sources, the attack may have been carried out with a Tochka-U ballistic missile or a multiple missile fire, which have not been fully confirmed. What is certain is that the Saratov was sunk (the Russians later managed to raise its wreck in 2023, but the ship was a total loss. The other two ships, Kunikov and Novocearkassk, suffered moderate damage and escaped then. (We will see, however, that both were eventually destroyed by the Ukrainians the following year on their second attempt – Kunikov in 2024 and Novocearkassk in December 2023. The Berdiansk attack demonstrated the vulnerability of Russian ships when in an advanced harbour, close to the front line, and was a moral boost for Ukraine.

Vasili Bîkov incident (March 2022)

In early March, Ukraine claimed to have sunk the Russian patrol vessel Vasily Bishkov (Project 22160), which had taken part in the assault on Snake Island. Video footage showed a ship targeted by coastal artillery or rocket fire south of Odessa. Later, on 16 March, Vasili Bishkov appeared in Sevastopol, refuting that claim. The episode highlighted the Ukrainian possibility of hitting even Russian patrol vessels, using camouflage and night strikes.

Diving of the Moskva Cruiser (13-14 April 2022)[19]

The defining event of 2022 in naval warfare – and possibly of the entire conflict – was the sinking of the Russian flagship Moskva. On the evening of 13 April, while about 100 km off the Ukrainian coast (south of Odessa, east of Snake Island), the Moskva was hit by two Ukrainian Neptun land-launched anti-ship missiles. The Ukrainian-produced R-360 Neptun missiles were a newly introduced weapon (derived from the Soviet Kh-35 model, with an extended range of ~300 km) and had never before been used in combat. The strikes caused a catastrophic fire aboard the cruiser, which was also carrying high-calibre anti-ship missiles and anti-aircraft ammunition. Internal explosions paralysed the ship. The crew – made up of more than 500 sailors – sent messages for help. Other nearby Russian ships and rescue services intervened, but on the night of 13/14 April, in rough seas, the Moskva capsized and sank.

Figure 3 is the impact image. Non-copyrighted photo

For Russia, the loss of the cruiser Moskva was a colossal blow with multiple implications:

- The Moskva was an iconic flagship, the flagship of the Black Sea Fleet and once the pride of the Soviet Navy (it was launched in 1979 as Slava). It had a displacement of more than 12,000 tonnes and was Russia’s largest and best-armed warship in the Black Sea. Its sinking “destroyed the Russian Navy’s sense of invulnerability” and induced reluctance among Moscow strategists to take risks at sea.

- In tactical terms, the Moskva was equipped with long-range anti-aircraft systems (S-300F and Osa-M) which provided an ‘umbrella’ of air defence for the entire Russian naval group in the area. Until then, other ships relied on the Moskva for early warning and protection against enemy aircraft or missiles. Once this ship was lost, the rest of the fleet became much more exposed. One Ukrainian officer claimed that the Moskva was “the key to Russian domination of the Black Sea” – a key that the Ukrainians had just thrown on the seabed.

- Exact human casualties remain controversial. Officially, Russia has admitted only 1 dead and 27 missing, claiming that the rest of the crew had been evacuated. Independent Russian sources (Novaya Gazeta) estimated at least 40 sailors killed, while some Western reports speculated a much higher toll (up to several hundred). The ship’s captain, Anton Kuprin (confirmed dead by Ukrainian sources), was among the casualties, and survivors later gave accounts of the chaos on board.

- Russia’s morale and image have suffered a severe shock. The Moskva is the largest battleship sunk in combat since 1945. The incident has demonstrated to the world the vulnerability of large ships to modern missiles, especially when these ships are not protected by effective anti-aircraft defences or evasive manoeuvres. The UK’s defence chief commented in late 2022: “Russia’s dominance in the Black Sea has now been called into question”.

From the perspective of the Ukrainian campaign, the sinking of the cruiser Moskva was a huge military and psychological achievement. It demonstrated that, using indigenous technology (Neptun missiles) and clever tactics (probably a radar diversion, given that the Russians were taken by surprise), Ukraine could strike at the very heart of the Russian fleet. The operation was also aided by Western intelligence, according to US media sources – NATO satellites and surveillance planes (P-8) tracked the Moskva’s position, and Ukraine would have received targeting clues (although these details are not officially confirmed in the sources cited, the US is known to have provided Ukraine with intelligence information during the conflict). After the sinking of the Moskva, the Russian Navy was forced to “significantly scale down its operations in the face of an adversary with far inferior naval capabilities”. The Russians became much more cautious near the Ukrainian coast.

Snake Island campaign and other blows (May-June 2022)

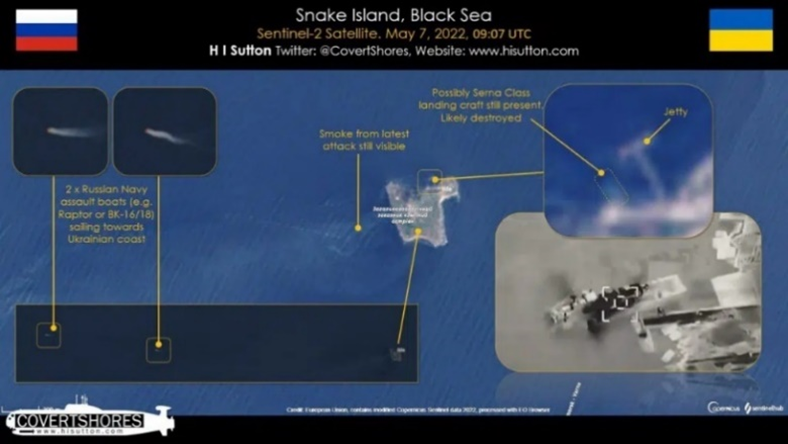

Following the loss of Moskva, the Russians continued their incursions into the waters around Odessa for a while, but “in a different pattern, of shorter range and duration, generally around Crimea”. Basically, they began to avoid the north-western Black Sea, now considered extremely dangerous. The Ukrainians have stepped up their attacks on the Russian garrison on Snake Island, using Turkish-made Bayraktar TB2 Bayraktar TB2 drones and precision artillery. Russian anti-aircraft defences on the tiny island (Tor and Pantsir systems brought there) proved insufficient: TB2 drones managed to destroy, in late April and May 2022, several targets on and around the island – including fast landing craft (at least one Serna[20] was pulverised by a drone in May, with the images going viral), a Mi-8 helicopter full of troops as it landed, and even anti-aircraft vehicles stationed on the island. These strikes have eroded Russia’s ability to hold onto Snake Island.

Fig. 4: An infographic showing the wreck of the Serna-class landing craft and the fleeing boats (Source: H I Sutton, used with permission)

One notable blow was the sinking of the rescue tug Vasili Beh (SB-739)[21] on 17 June 2022. Vasili Beh was carrying personnel and equipment (including an anti-aircraft system on Snake Island when it was targeted by Ukraine. According to Ukrainian sources, the ship was hit by two Western Harpoon anti-ship missiles recently delivered by Denmark. The Harpoons hit the tugboat head-on, sinking it despite the fact that it was supposedly defended by the Tor system on board. The incident showed that once Ukraine received state-of-the-art anti-ship missiles from the allies, even the smaller Russian support ships were not safe.

Fig. no.5: The second anti-ship missile headed towards the Russian tug immediately after the first one caused an explosion (Screenshot from images recorded by TB2 Bayraktar UAV)[22]

Moreover, after the sinking of the tug, Harpoon missiles were also used against Russian-owned offshore oil platforms (the so-called “Boiko towers”[23] off Crimea, equipped with Russian surveillance radars); the strike of those platforms in June 2022 further degraded the Russian device’s image of invulnerability.

Fig. No.6 The drilling platforms known as “Boiko Towers”- Photo via X / Nexta

Under these pressures and suffering heavy losses of men and assets in the Snake Island area, Russia decided to withdraw. On 30 June 2022, Russian troops and technology were evacuated from Snake Island and the island returned to Ukrainian control. Moscow claimed it was a “goodwill gesture” to facilitate Ukrainian grain exports, but the widely recognised reality was that maintaining the island had become militarily impossible and was a “victory for Ukrainian drones and missiles”. The withdrawal from Snake Island completely eliminated the threat of a Russian landing in Odessa and marked Russia’s strategic failure to control the north-western Black Sea.

In summary, the year 2022 began with Russia on the naval offensive, but ended with Russia cautious and partly on the defensive at sea:

- The loss of Moskva drastically reduced the Russian fleet’s range and aggressiveness.

- Ukraine, though without significant warships, has compensated with mobile coastal systems and air strikes/drone strikes, turning part of the Black Sea into a “no-go zone” for Russian warships.

- Russia was forced to accept a diplomatic arrangement for Ukrainian grain exports – the Black Sea Grain Initiative brokered by the UN and Turkey, which came into force on 22 July 2022[24] . This agreement created a secure maritime corridor for merchant ships from three Ukrainian ports, which implicitly meant that Russia could not fully control Black Sea traffic without coming into direct conflict with Turkey and the international community.

- Russian forces have begun to strengthen the defences of their Crimean ports. After the 2022 maritime drone attack (see next section), Russian submarines were moved from the exposed base at Sevastopol to the more sheltered Novorossiysk harbour in the Caucasus. For fear of further Ukrainian attacks, some of the Black Sea Fleet’s assets have been moved away from the conflict zone, diminishing the fleet’s ability to project force.

Towards the end of 2022, it was becoming clear that the “Russian fleet was failing to assert itself” in the war against Ukraine, despite its initial superiority. The next chapter will analyse developments in 2023, a year in which Ukraine expanded its use of new technologies (notably naval drones and Western missiles) and administered even greater losses to Russia, putting its fleet in a critical situation.

4. The year 2023 – Russia’s Black Sea Fleet in the Black Sea is in sharp decline

If in 2022 Russia suffered its first shocks at sea, 2023 brought an escalation of naval conflict and a series of spectacular strikes against the Russian fleet. Ukraine diversified its means of attack, introducing autonomous naval drones and obtaining from allies long-range aerial cruise missiles (such as the Storm Shadow/SCALP) that could strike harbours used by the Russians. Russia, for its part, tried countermeasures: it moved ships to safer harbours, used barges and nets to protect bases, and increased the use of naval aviation in the Black Sea.

However, the overall trend in 2023 was unfavourable to Russia – its Black Sea fleet continued to lose units and freedom of manoeuvre. By the end of the year, as the British Defence Secretary noted, some 20% of the Black Sea Fleet had been destroyed in the last 4 months, seriously questioning Russian dominance in the region. Let us review the main events.

Russian consolidation and first drone strikes (January-June 2023)

In the first half of 2023, Russia endeavoured to consolidate its naval positions after the previous year’s losses. At the beginning of the year, the Russians still had a significant number of operational warships in the Black Sea: the flagship frigate Admiral MakarovEssen (one of them taking over the role of the fleet’s flagship after the loss of Moskva), missile-carrying corvettes (Buyan-M), several patrol and desant ships, and Kilo submarines. They have continued to launch Kalibr missile attacks from these naval platforms towards land targets in Ukraine. Every time Russia prepared a missile attack, ships and submarines were observed leaving the harbours (Ukraine frequently reported how many Kalibr launchers are present in the Black Sea, for example in January 2023 announcing that Russia has 4 Kalibr-carrying ships ready to attack).

Still, the Russians have become cautious: after the October 2022 incident (when a Ukrainian maritime drone strike at Sevastopol lightly damaged at least one minesweeper), many major ships have been moved to Novorossiysk or kept under cover behind barrage of nets and barges. The installation of anti-drone nets at the entrance to Sevastopol harbour, the use of smoke masking systems to hide targets and increased air patrols over Crimea were all part of the new Russian defensive posture.

Meanwhile, Ukraine is developing new offensive means. In particular, a flotilla of autonomous naval drones – small, fast unmanned surface vehicles (USV – Unmanned Surface Vehicles) loaded with explosives and guided to the target remotely – has been created. A first demonstration of the potential of these weapons took place on 29 October 2022, when Ukraine launched a combined attack with 7-9 naval drones and several aerial drones on the Sevastopol naval base. This was the first attack of its kind in history: the maritime drones (each the size of a larger skyjet, with several hundred kg of explosives) attempted to penetrate the harbour and strike the docked ships. The Russians managed to destroy some of the drones before impact, but at least one minesweeper – the Ivan Golubeț – was damaged, and there are indications from the frigate Makarov (also targeted) that a drone filmed at very close range before being neutralised. The October 2022 attack didn’t sink any large ships, but it showed a profound change: even the Russian Fleet’s main harbour, Sevastopol, was no longer a safe sanctuary.[25]

In 2023, Ukraine perfected this capability. In January-February, isolated incidents continued (for example, on 16 January 2023 Russian air defences in Sevastopol shot down a drone, a sign that attacks were frequent). But major naval drone strikes returned in the summer:

- On 22 March 2023, three Ukrainian maritime drones struck again off Sevastopol. Russia claimed to have neutralised them before they hit their targets, but reports indicated explosions in the area.

- On 24 May 2023, the Russian radio reconnaissance vessel Ivan Khurs (Project 18280) was attacked by maritime drones in the Black Sea north of the Bosphorus while returning from the Mediterranean. Ukrainian video footage showed a drone approaching and possibly hitting the ship. Russia claimed that the Ivan Khurs suffered only minor damage and arrived safely in Sevastopol[26] . However, the attack hundreds of kilometres off Ukraine’s coast demonstrated the extended range of drone operations.

A turning point was the Ukrainian summer offensive of 2023. In parallel with ground actions, Ukraine stepped up its naval campaign. On 17 July 2023, on the very day Russia announced the termination of the Grain Deal, the Ukrainian Security Service (SBU) again attacked the Crimean (Kerci) Bridge using two naval drones loaded with explosives, managing to damage a portion of the roadway. The attack underlined the technological maturity of these drones, dubbed “Sea Baby”, developed in secret by the Ukrainians.

Also in mid-2023, Ukraine began the gradual recapture of its “eyes” in the Black Sea – it recaptured or neutralised several Russian-occupied offshore platforms and surveillance buoys, thus regaining intelligence-gathering advantages. For example, in August 2023 there were clashes over the “Boiko” drilling platforms, and a raid by Ukrainian special forces flew the flag on one of them. These actions extended the range of Ukrainian sensors, allowing early detection of the movements of Russian ships. All in all, the first part of 2023 was marked by constant harassment of the Russian fleet, mostly by new means. Russia retaliated by hitting[27] harbour infrastructure whenever it could (including after the grain agreement was abandoned, it intensively shelled the ports of Odessa, Chornomorsk, Reni, Izmail). But more and more, the initiative at sea seemed to shift to Ukraine’s side, which was striking selectively and giving clear messages that no Russian ship was out of its range.

Major strikes against the Russian Fleet (August-September 2023)

The second half of 2023 brought Russia’s worst losses since the sinking of the Moskva. A series of well-coordinated Ukrainian attacks, and their use of high precision, hit Russian warships either at sea or directly at their bases in Crimea. We will detail these key incidents:

(i) Attack of Novorossiysk (4 August 2023)

In the early hours of 4 August, several Ukrainian naval drones attacked the Russian port of Novorossiysk (Krasnodar region), which had become an important haven for Black Sea Fleet ships. The main target was the Olenegorski Gornyak (Project 775 Ropucha), a large decommissioned ship temporarily stationed here. The attack was captured on video and partially confirmed by the Russian side itself: the Olenegorski Gornyak was hit and seriously damaged, being seen tilted sharply to one side (port side) while being towed to the berth by the Russians. Ukrainian sources suggested that the vessel was so badly damaged that it was virtually inoperable (the equivalent of a partial sinking)[28] . The Olenegorski Gornyak was a Northern Fleet decommissioned ship on loan to the Black Sea Fleet for the invasion; ironically it became the second largest Russian ship disabled by Ukraine after the Moskva. The attack on Novorossiysk was significant for another reason: it showed that even Russian ports are not immune. On the same night, another group of drones struck a Russian oil tanker (Sig) near the Kerch Strait, damaging it. These operations directly targeted Russian logistical and energy transport infrastructure, signalling the escalation of the naval conflict in the wider Black Sea.

(ii) Destruction of ships in dry dock at Sevastopol (13 September 2023)

One of the most devastating blows to the Russian fleet came at dawn on 13 September. Ukraine launched an attack with Storm Shadow/SCALP cruise missiles (delivered by Britain and France) on the Sevastopol shipyard. The missiles accurately hit a dry dock where two Russian naval vessels were undergoing repairs: the diesel-electric submarine Rostov on Don (B-237, Project 636.3 Kilo Upgraded) and the large decommissioned ship Minsk (BDK- Minsk, Project 775 Ropucha)[29] . The result was impressive: both ships were severely damaged, virtually knocked out of action. Satellite images after the attack showed the Rostov-on-Don submarine with a massive hole in its midsection, the hull having been pierced by the explosion. The Storm Shadow missiles probably directly hit the submarine and dropship, causing detonation of munitions and devastating fires. Western sources assessed that the submarine is “damaged beyond economic repair” – in other words, it is unlikely to ever be operational. The Minsk has also suffered irreparable damage (destroyed structure and machinery). This was the first time since World War II that a Russian (or Soviet) submarine was destroyed by the enemy. The loss of a modern submarine and a landing ship in a single strike seriously undermined the capability of the Black Sea Fleet. A UK Ministry of Defence report noted that repairs would take many years and that Russia’s ability to launch cruise missile attacks from the sea was affected, as Rostov frequently launched Kalibr missiles.

(iii) Striking of Fleet Headquarters in Sevastopol (22 September 2023)

Less than two weeks after the dock attack, Ukraine symbolically and operationally targeted the Russian fleet command centre. On 22 September, in broad daylight, a salvo of missiles (presumably Storm Shadow/SCALP) hit the Black Sea Fleet Headquarters building in Sevastopol[30] . Dramatic video footage shows the moment of impact, with a missile penetrating the building and a huge explosion devastating it. Ukraine has officially confirmed the attack, calling it a “successful strike” on the fleet headquarters. The command and human casualties were kept secret by the Russians, but Ukrainian sources initially claimed that dozens of officers, including the fleet commander, Admiral Viktor Sokolov, had been killed or wounded. Moscow denied the admiral’s loss, later showing footage of him in a video conference (the veracity of which has been debated). What is certain is that the Fleet General Staff was seriously affected – the historic building was partially destroyed, and the leadership of the fleet was certainly shaken. According to reports in October, Commander Sokolov was nonetheless replaced/dismissed following these failures, although Russian officials have not publicly announced the change. The hit on the Fleet headquarters had a major psychological impact: it demonstrated that Ukraine can touch the symbolic heart of Russian naval power in Crimea, even under the nose of Russian anti-aircraft defences and aircraft.[31]

Destroyed building on the territory of the Russian Black Sea Fleet Command Communications Centre 744, satellite image by Planet Labs, Source Photo: Radio Liberty.

These attacks in August-September 2023 confirmed the sharp degradation of the Russian Fleet. Within weeks, Russia lost:

- a submarine and two large landing craft (one at the dock, one at Novorossiysk),

- a modern patrol ship (we’ll see in a moment, Sergey Kotov, in early 2024, was destroyed),

- a reconnaissance ship temporarily out of action (Ivan Khurs),

- Coastal air defence installations in Crimea (for example, on 23 August 2023, Ukraine destroyed an S-400 Triumf system at Cape Tarkhankut, weakening the fleet’s anti-aircraft cover in western Crimea),

- Fleet Headquarters as infrastructure and perhaps key personnel.

Commentators noted that “the Russians are very worried about these attacks”, starting to move their ships even further out to harbours in the Sea of Azov, which was exactly what the Ukrainians were after. Many Russian ships were hit either at sea or on shore, forcing them to stay as far away from Ukraine as possible. Basically, by the end of September 2023, the Russian fleet was in retreat[32] – geographically (moving east, out of range of Ukrainian systems) and in activity level (drastically reducing offensive patrols).

Impact on the fleet and situation at the end of 2023

By the end of 2023, Russia’s Black Sea Fleet is in an unprecedented defensive posture:

- Confirmed losses – According to the UK Ministry of Defence (Grant Shapps) and other sources, about a fifth of the fleet’s warships had been destroyed or severely damaged from June 2023 to October 2023. This estimate of 20 per cent in four months, also cited by the international press, emphasises the intensity of Ukrainian strikes by the end of 2023. Among the ships lost were: Olenegorsky Gornyak (Ropucha, critically damaged), Minsk (Ropucha, destroyed), Novocearkassk (Ropucha – we will mention the last strike in December immediately), Caesar Kunikov (Ropucha – still operational at that time, but damaged earlier at Berdiansk), Saratov (Tapir, lost in 2022), Moskva (cruiser, lost in 2022), Rostov-na-Donu (submarine Kilo, destroyed), Askold (modern corvette, destroyed in November), plus various smaller craft and support ships.

- Moving assets – After repeated strikes in Crimea, Russia relocated many of its units. The remaining submarines continued to operate out of Novorossiysk (e.g. Veliki Novgorod and Kolpino), where they were still threatened by attacks (unexplained explosions were also reported at Novorossiysk). Some surface vessels took refuge in the harbour of Feodosia (eastern Crimea) or in the Sea of Azov (Mariupol and Kerci harbours), linked to the rest of the fleet through the Kerci Strait. At Mariupol, patrol vessels and small landing craft were observed far from the range of Ukrainian maritime drones.

- Attempts at dispersal and protection – The Russians have taken improvised measures: anchoring old barges and ships at harbour entrances to physically block naval drones, installing anti-torpedo nets around important ships, and creating smoke screens on attack alerts. They also began to make increasing use of Naval Aviation patrol and fighter aircraft – as a report in October 2023 noted, Russian naval aviation has taken on an increasingly important role, using Ka-27 helicopters and Su-30 aircraft in drone search and anti-ship attack missions[33] . This was a tacit recognition that Russian surface ships could no longer operate safely and that the Russians were relying on aerial alternatives.

- More late losses – In the very last days of 2023, Ukraine struck another blow: on 26 December, Ukrainian aircraft launched missiles (Storm Shadow, according to sources) over the Crimean port of Feodosia, hitting the destroyer Novocearkassk (BDK-46). Successive explosions and fire indicated the detonation of ammunition on board, and Ukrainian sources said the ship was totally destroyed. Although Russia has not officially confirmed the sinking, satellite images showed Novocearkassk virtually gone, with debris still visible. According to Radio Free Europe, even a nearby training ship (UTS-150) was partially submerged by the blast. Again, there were casualties. Thus, Novocearkassk, which had survived the damage in 2022, was sunk on the second attempt in 2023.

By the end of 2023, the Russian Black Sea Fleet was severely undermined. As noted analyst Pascal Ausseur[34] , “Today, there is no Ukrainian or Russian warship in the Black Sea [that can operate freely]. Because it is detected, tracked and targeted if you want. This is the first war where things have got to this point.” Basically, Russia had become unable to use the Black Sea for force projection or naval offensive operations. Its ships were hiding in distant harbours, and any sortie on the open seas carried enormous risks.

It should be noted that the damage to the fleet also affected the overall Russian strategy: in the absence of safety at sea, the Russians stepped up land-based alternatives. They withdrew from the grain agreement on 17 July 2023, attempting to subjugate Ukraine’s economy by total blockade. Ukraine responded by opening an alternative maritime corridor off the coasts of Romania and Bulgaria in defiance of Russian threats. Russia failed to ban navigation in this corridor altogether, partly because of fear of hitting neutral ships and partly because its fleet could no longer venture to impose a blockade near NATO waters.

Thus, the balance sheet of 2023 for Russia has been bleak on the naval front: severe material losses, loss of strategic initiative, degradation of its image as a maritime power, and potential changes of command (amid repeated failures, with the fleet commander and other officers likely to be sanctioned). Russia has sought workarounds, such as announcing its intention to establish a naval base in Abkhazia (Georgia) – far out of Ukrainian range – as Politico reported in October 2023[35] . However, analysts pointed out that the port of Ochamchire in Abkhazia is rudimentary and unsuitable for large ships, so it cannot replace Sevastopol. The intention, however, emphasises Moscow’s desperate effort to reassert its naval presence in the Black Sea, whereas at Sevastopol it had become precarious.

In the next chapter we will continue the analysis with the events of 2024 and the situation today (2025), where we will see that the trend has continued: Russia has lost its remaining naval advantage as Ukraine has introduced new capabilities (such as the US-supplied ATACMS ballistic missiles) in naval combat.

5. The year 2024 – Russian fleet in the Black Sea almost completely neutralised

After the heavy blows suffered in 2023, the entry into 2024 found the Russian fleet fragile and on the defensive. Ukraine did not stop its campaign, however, and the first months of 2024 brought spectacular new attacks that sank the last major ships Russia still relied on in the Black Sea. The year 2024 virtually confirmed the operational collapse of the Russian fleet in the region: by its mid-year, Russia had no Kalibr missile carriers afloat in Crimea, and the only remaining launch platforms were submarines (also reduced in numbers) and aircraft. We will review the main events of 2024, although it should be noted that, as this is still an ongoing year (until April 2025 for the purposes of this study), the available information is less and sometimes contested.

Continuation of naval drone attacks (January – March 2024)

In the first months of 2024, Ukraine continued its successful use of naval surface-to-surface drones (USVs) against Russian vessels. Two major incidents are worth highlighting:

- Attack on the corvette Ivanovets (31 January / 1 February 2024)[36]

At the end of January, special units of the Ukrainian Defence Intelligence Directorate (GUR) – presumably the special forces group “Group 13” – executed a complex attack with a swarm of naval drones on the Russian corvette Ivanovets (Pr.1241 Molny/Tarantan, a small bastion carrying anti-ship missiles). The operation took place off the Crimean coast at night. Multiple unmanned explosive craft were used to surround and attack the corvette. A black-and-white video clip released by Ukrainian services shows dramatic footage of the Ivanovets being surprised by the explosions and then listing and sinking. On 1 February, Ukraine officially announced that Ivanovets had been destroyed in the attack, which was also unofficially confirmed by Russian sources on Telegram. Later, Western officials said it was believed the ship was indeed sunk. The significance of this incident is major: the Ivanov was one of the last two corvettes equipped with anti-ship missiles in the Black Sea Fleet. By eliminating it, Ukraine has once again demonstrated the vulnerability of the Russian fleet, even escorted ships, to drone swarm attacks. The ship’s estimated value was $60-70 million, but its key feature – speed and manoeuvrability – did not save it. In addition, there were an estimated ~40 sailors on board; the Russians have not released anything about their fate, but it is likely that there were human casualties given the violence of the attack.

Fig. no.7: collage by Defence Romania

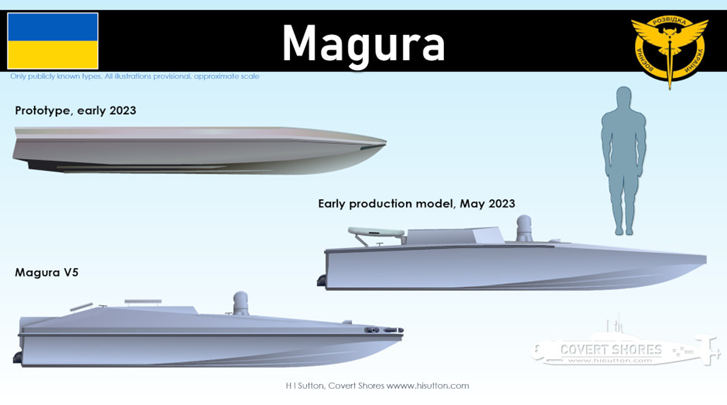

- Attack on patrol vessel Sergey Kotov (4/5 March 2024)[37]

Sergey Kotov (Pr. 22160, modern ocean patrol vessel, entering service in 2021) became the next target. This ship was used by the Russians for patrolling and escorting convoys of ships after the termination of the Grain Agreement – for example, patrolling the eastern mouth of the Black Sea, it monitored potential routes of Ukrainian ships. On the night of 4 to 5 March 2024, according to GUR information, a strike by the Magura V5 naval drone group Magura V5 hit Sergey Kotov near the Kerci Strait. GUR reported that the ship suffered damage to its stern, port and starboard sides, totalling damage of more than $65m. Ukrainian Navy spokesman D. Pletenciuk, said on TV that “now the ship is lying on the seabed” as a result of direct hits by drones. It has also been reported that Sergey Kotov was carrying a Ka-27 (or Ka-29) helicopter at the time of the attack, suggesting that the explosion may have also destroyed the aircraft. Russia has not confirmed the incident, but the independent Astra channel reported rumours about the loss of the ship. On 27 March, Ukrainian sources broadcast images of the wreckage on the seabed of a ship that appeared to be Sergey Kotov. If this sinking is confirmed, it is highly significant: the Sergey Kotov was one of the newest Russian ships in the Black Sea and the only one of its class (the second identical unit, the Pavel Derzhayvin, had been damaged earlier). The Russians would thus have lost virtually all modern surface ships capable of launching cruise missiles. Shortly afterwards, a Ukrainian press release emphasised that there were no Kalibr surface-to-surface missile carriers in Sevastopol.

Fig.no.8: real pictures…suggestive, no copyright

These two attacks – Ivanovets and Sergey Kotov – showed that Ukraine, though worn down by a year of fighting, entered 2024 with fresh forces and improved tactics, hitting the enemy exactly where it still had some offensive power. The Russian fleet, after these incidents, has basically become a “coastal defence” fleet with no real sea combat capability.

ATACMS and Storm Shadow missile strikes (May – November 2024)

By autumn 2023, the Western allies had supplied Ukraine with other long-range weapons, notably MGM-140 ATACMS (US) tactical ballistic missiles with a range of ~300 km (submunitions variant) and Franco-British SCALP-EG (similar to Storm Shadow) air-to-air cruise missiles. Ukraine had until then lacked the ability to strike precise targets at long distances at sea. With these systems, it was able to expand its target list.

The defining event of the year 2024 (so far) was the destruction of the corvette Ciclon[38] – the Black Sea Fleet’s last newly-built bastion capable of launching Kalibr missiles. The Tsiklon (Tsiklon) was a Karakurt-class corvette (Project 22800), built at the Zaliv shipyard in Kerci and not entering service until July 2023. This modern ship (70 crew members, capable of carrying 8 Kalibr missiles and equipped with the Pantsir-M air defence system) was the pride of the new Russian naval production, intended to replace the losses. But on 19 May 2024, Ukraine struck the port of Sevastopol by surprise, using two long-range ATACMS missiles (according to Russian military bloggers). The target: the corvette Țiklon, which was berthed. The result: according to the Ukrainian General Staff, the Țiklon was directly hit and completely destroyed. Initially, the claim showed that a minesweeper (Kovrovets) had been hit , but this has been revised: the real target was the Țiklon, confirmed by independent Russian sources and subsequent images, and that the Țiklon was sunk or damaged beyond repair, marking the last Russian surface Kalibr launcher in Crimea. A Ukrainian spokesman emphasised that after the destruction of the Țiklon, “there are no more surface-to-surface cruise missile carriers based in Crimea”. Confirmation also came from the Russians, who although officially silent, through Telegram channels acknowledged the hit, and the Russian military for a week organised “search-and-rescue” operations in the area of the wreckage of the Țiklon, a sign that the ship was lost.

Fig. no.9 Corvette Țiklon,

Also in autumn 2024, there were reports of other naval targets being hit. The Ukrainians sank in Sevastopol the Russian submarine Rostov on Don[39] , which was undergoing repairs after having been hit in December on 13 September 2023 and was reportedly targeted in Sevastopol harbour by a SCALP missile, but details remain uncertain and unconfirmed. Oil platforms off Crimea were again attacked (with Ukraine consolidating its control over some of them).

Fig. no.10:Russian submarine Rostov on Don hit dock

In the absence of any Russian naval reaction (the Russian fleet practically stopped going to sea), the maritime conflict in the second half of 2024 focused more on attacking maritime infrastructure and trade. Russia continued to hit Ukrainian ports on the Danube (Reni, Izmail) with Iranian drones, seeking to sabotage Ukrainian exports. In turn, Ukraine retaliated by striking Russian economic naval targets: on 12 August 2024 Ukrainian naval drones struck the Russian tankers Sig (second attack on it) and Afanasi Nikitin, causing damage.

Another aspect of the 2024 campaign was Ukraine’s intensification of special maritime operations: commando raids on the Crimean coast, infiltrators for sabotage (such as putting explosives on ships in port – there were rumours that some mysterious explosions in the port of Sevastopol in 2024 were direct sabotage actions). All these operations keep the Russian fleet under constant tension.

By the end of 2024, the picture was clear: Russia had lost the ability to use its Black Sea fleet effectively in war. With the exception of submarines and aviation, the rest of the naval components were either destroyed or forced into inaction:

- Two frigates (the Makarov and Essen) had physically survived, but were staying withdrawn and avoiding engagement by being converted into occasional cruise missile batteries, launching Kalibr from close to the Russian shore. There is speculation that one of them may have left the Black Sea before the Bosphorus closed (but this is uncertain; the frigate Admiral Grigorovich is known to have been stuck in the Mediterranean and not returned).

- The remaining dropships (two Ropucha: Orehovo-Zuevo and Yamal, plus smaller ones) were hidden in Azov harbours or eastern Crimea. They could no longer carry out offensive missions anyway, with vulnerable bases and depots.

- The Russian coastal patrol forces in Crimea have been reduced to small boats and armed barges – for example, the Russians have adapted some civilian vessels to patrol the Kerci Strait after the loss of military vessels, and have even armed fishing boats or tugs for security tasks.

- The only formidable naval weapons left were the Kilo submarines (of the original 6: Rostov destroyed, Veliky Novgorod and Kolpino active, Novorossiysk, Krasnodar, Stary Oskol possibly active – some may be in overhaul). These submarines periodically launched Kalibr missiles from the deep, making them harder to intercept. However, they too were under surveillance: NATO sent P-8 Poseidon patrol aircraft to the Mediterranean and the international Black Sea to monitor submarines as they surfaced. In addition, the sinking of the Rostov showed that the docks are not safe for them either.

6. The situation in early 2025

By the first quarter of 2025, the strategic naval situation in the Black Sea area can be summarised as follows:

- Russian Black Sea fleet largely neutralised

It can no longer operate freely in the western and central Black Sea. Areas off the coasts of Ukraine, Romania and Turkey are virtually off-limits to Russian ships, due to Ukrainian surveillance and weapons range. The Russians limit themselves to a maritime strip near Eastern Crimea and the Caucasus .[40]

- Russian maritime trade remains at risk

After the collapse of the grain deal, Russia declared any ship bound for Ukrainian ports as a potential target, and Ukraine issued a symmetrical warning against ships bound for Russian ports. In practice, Ukraine has attacked several Russian cargo ships (including in harbours), and Russia has searched or intimidated several neutral merchant ships en route to Ukraine. Direct confrontation was limited, however, as both sides risked complicating the successful establishment of a new naval corridor for exports by sailing close to Romanian and Bulgarian territorial waters. Russia did not attack ships in that area, fearing an incident with NATO. Thus, Moscow’s plan to completely strangle Ukrainian exports partially failed. For its own exports (oil, grain), Russia began to depend more on the ports on the Sea of Azov (e.g. the port of Kavkaz, from where ferries and barges cross the Kerch Strait to new railway routes and pipelines. The Ukrainian attack on the Crimean Bridge (July 2023) and subsequent ones have made logistics on land more difficult, increasing the role of local shipping (Azov-Crimea ferries). But these ferries are vulnerable to drones, so the Russian logistical situation remains precarious.

We note that by the end of the period under study (2022-2025), Russia has suffered a strategic naval collapse in the Black Sea. Instead of projecting power, the Black Sea Fleet became largely immobilised and reduced to local defence roles. As one military analyst has concluded they have not realised that they have lost 20% of their fleet in a matter of months“[41] , and their historical dominance in the Black Sea is seriously in doubt. In Appendix 1 I have detailed and fully represented Russian naval losses.

In the following chapters we examine the broader implications of these events: how they affect Russia’s economic security and its capacity for strategic maritime projection, what role Ukraine’s new technologies and innovative tactics have played in achieving these successes, and, last but not least, what lessons are being learnt for Russia’s naval doctrine and for the world’s maritime powers.

7. Impact on Russia’s strategic maritime projection and economic/logistical security

Russia’s strategic naval naval collapse in the Black Sea has consequences beyond the immediate military framework. The Black Sea Fleet has traditionally been an instrument of regional influence and protection of Russian economic interests in the Pontic Basin and beyond (the Mediterranean). The severe weakening of this fleet and the loss of freedom of action at sea affects Russia’s ability to project its maritime power as well as the security of its trade and supply routes.

Diminishing Russia’s strategic maritime projection

Before the war, Russia used the Black Sea Fleet not only for local tasks but also as a bridge to the Mediterranean. Its ships would regularly pass through the Bosphorus (under peacetime Montreux rights) to join the Russian 5th Operational Squadron in the Mediterranean, supporting operations such as the one in Syria (Tartus naval base). With the closure of the straits by Turkey to belligerent vessels (from February 2022), the Black Sea Fleet became a captive in its own theatre. Worse, however, after its losses, the fleet cannot even project power inside the Black Sea.

A few points:

- Inability to militarily threaten NATO littoral states

At the outset of the invasion, questions were being asked whether Russia would challenge freedom of navigation in the Black Sea, possibly by denying access to NATO ships or exerting aggressive pressure (such as the 2021 incident with HMS Defender near Crimea[42] ). In 2022-2023, however, the situation was reversed: Russian naval vessels avoided approaching Romanian or Turkish territorial waters for fear of being monitored and possibly attacked. Russia could no longer afford direct provocations to NATO in the Black Sea, given the delicate context. As a result, Russia’s influence on NATO’s south-eastern flank has diminished. Instead, NATO has increased its aerial surveillance presence (AWACS, drones, P-8 aircraft) and helped to counter mines, providing a greater indirect presence.

- Reducing influence in the Mediterranean and Middle East

The Black Sea Fleet supplies a good proportion of the ships Russia deploys in the Mediterranean. For example, the cruiser Moskva had been deployed in 2015 off Syria, launching missiles and providing anti-aircraft defence. After the loss of the Moskva and the Montreux restrictions, Russia remained in the Mediterranean with what ships it already had there (some from the Northern, Pacific and Baltic Fleet deployed before the conflict). Without the ability to send for fresh rotation through the straits, the Russian naval presence in the Mediterranean has stagnated.

Black Sea Fleet ships in the Mediterranean were stuck there (e.g. the frigate Admiral Grigorovich), and those in the Black Sea inland could not get out to replace them. With the sinking of the Moskva, Russia also lost the only truly “ocean calling” ship in the Black Sea, reducing its ability to carry out remote missions. In addition, the Black Sea Fleet was tasked with protecting Russia’s southern flank and projecting power towards the Balkans and the Middle East. By undermining this fleet, Russian strategists had to compensate with the Northern and Pacific Fleets (sending additional units to the Mediterranean on long, circuitous routes via Gibraltar or the Suez Canal). The costs of these measures are high and the Russian naval presence in the Mediterranean has weakened. Thus, Russia has fewer means to directly influence events in areas such as Syria, Libya or the eastern Mediterranean compared to pre-2022.

- Limiting regional deterrence and response

The powerful Black Sea fleet gave Russia options in a wide range of scenarios – from rapid military intervention (such as a possible landing in Odessa) to reacting to regional crises (e.g. responding to naval incidents around the Bosphorus, pressuring Georgia, etc.). With the losses incurred, these options were drastically reduced. In the autumn of 2023, the Kremlin resorted to indirect threats – for example, announcing plans for a naval base in Abkhazia (Georgia) – partly in reaction to the diminishing Black Sea Fleet. But experts have noted that such a base would be of marginal importance, given limited logistics and geography. In other words, Russia has lost some of its regional leverage. The Black Sea Fleet can no longer, for example, credibly threaten a breakout in the Bugeak or Odessa (which used to keep Ukrainian forces busy), nor can it intimidate littoral states with large naval exercises. Russia’s historical dominance in the Black Sea basin is now being challenged or even, as Grant Shapps put it at[43] , “questioned”.

- Forcing Russian ships to shelter away from the conflict zone

Through the blows they have suffered, the remnants of the Black Sea Fleet have moved eastwards, to harbours like Novorossiysk or even the Sea of Azov. This has strategic implications: the further they stay towards the Sea of Azov, the less influence they have on the western part of the Black Sea. Basically, Russia has “pushed” its own fleet into the north-eastern corner of the Black Sea, leaving the north-western part under the de facto control of NATO/Ukraine sensors and weapons. This is a remarkable reversal from the situation in February 2022, when Russia was dictating terms across the Black Sea.

The collapse of the Black Sea Fleet has considerably weakened Russia’s ability to project naval power. Although the Northern and Pacific fleets remain strong in other theatres, the importance of the Black Sea cannot easily be offset, as it is Russia’s only access to the “warm seas” to the south. The loss of prestige and freedom of action here constitutes not only a military failure but also a geopolitical setback: Russia can no longer consider itself unchallenged in the ‘Black Sea fortress’.

Impact on Russia’s economic and logistical security

The Black Sea is not just a military theatre, but also a vital economic artery for Russia:

- Through the ports of Novorossiysk, Tuapse and Taman, Russia exports massive quantities of oil and petroleum products (essential routes for its budget).

- Also through the Black Sea, Russia exports grain and imports various goods (although some traffic has been re-routed via the Baltic or Pacific).

- Crimea, annexed in 2014, is logistically dependent on the bridge over the Kerci (Crimean Bridge) and the naval link with mainland Russia.

The conflict has significantly disrupted these aspects:

- Grain blockade and Ukrainian counter-blockade

From February 2022, Ukrainian ports were blockaded by the Russians, which created a global grain crisis as Ukraine was a major exporter of wheat, maize and vegetable oil. Under international pressure, the Grains Initiative was finalised (July 2022), allowing a controlled resumption of Ukrainian exports. Russia, for its part, benefited from the agreement because it allowed it to export its own agricultural production more easily (and to obtain promises to lift some agricultural sanctions). When Russia unilaterally withdrew from the agreement in July 2023, it hoped to strangle Ukraine’s economy and gain political leverage (possibly by blackmailing grain-dependent African/Asian countries with famine). However, Ukraine’s “Ukrainian military successes in the Black Sea” – sinking Russian ships and forcing the fleet to retreat – allowed Ukraine to counter the blockade. Ukraine opened an alternative maritime corridor in August 2023, sending grain ships on the route Odessa – Cape Sarych (Crimea) – Danube Delta – Romanian/Bulgarian coast, taking advantage of shallow waters where Russian submarines cannot operate. Although risky, this corridor has proven effective: by the end of 2023, the volume of Ukrainian exports through the new corridor has come close to the levels during the agreement. Thus, the Russian blockade has largely failed; Russia failed to completely halt Ukrainian exports, and in October 2023 even had to initiate talks (via Turkey and Qatar) on relaunching an agreement, signalling its desire to break the deadlock. By losing the fleet, Russia has also lost the “weapon of blockade” – it can no longer impose its will in the international waters of the Black Sea.

- Attacks on Russian export/import routes

Ukraine has demonstrated that it can strike not only Russia’s military but also its maritime economic targets. For example, the naval drone attacks on the Sig and Olenegorski tankers Gornyak Sig and Olenegorski Gornyak (also used to transport fuel) have shown the vulnerability of the Russian oil export circuit through the Bosphorus. One notable incident occurred on 16 November 2022, when an explosion (possibly a Ukrainian underwater drone attack) occurred at the Novorossiysk oil terminal. The British commented that if Ukraine can threaten the Novorossiysk harbour, it is “another strategic challenge” and would further undermine Russia’s maritime influence. These risks have prompted Russia to invest in the security of its oil ports, but also to expand its crude oil exports via other routes (to Asia via Baltic ports or by rail). Any increase in transport or insurance costs for Russian oil, caused by the risk of war in the Black Sea, hits the Russian budget directly. Also, the repeated attack on the Crimean Bridge (July 2023 and then October 2022, July 2023 – several times) temporarily disrupted logistical flows to Crimea. Ferry and train transport from the port of Kavkaz had to be restored under the threat of drones. Similarly, oil depots in Sevastopol and other locations have been hit by Ukrainian drones (e.g. a large fuel depot in Sevastopol burned down in April 2023). We are talking about strikes that affect Russian military logistics (supplying the fleet and troops in southern Ukraine is becoming more difficult) and create additional economic stress.

- Energy security and maritime critical infrastructure

The Black Sea is also home to gas pipelines and undersea cables. One scenario of concern is the possible extension of the conflict to these infrastructures. For example, Russia operates the TurkStream gas pipeline under the Black Sea to Turkey. If the naval situation had been different (if Russia dominated the sea), it might have threatened the infrastructure of Ukraine or others. But in reality, Russia now also fears for its own infrastructure given Ukrainian capabilities. For example, in late 2023 it was speculated that an explosion on the submarine cables between Crimea and Krasnodar could have been a Ukrainian special operation (not officially confirmed). Regardless, Russia needs to re-evaluate the security of its Black Sea infrastructure with limited resources, given that its fleet has been decimated.

- Crimean economy and tourism

One aspect often overlooked is the effect on Crimea, which Russia turned after 2014 into a military base as well as a tourist destination for Russians. The war drove tourists away completely (especially after missiles and drones started dropping on the peninsula), hurting the local economy. The blockade of maritime transport also reduced the volume of goods through Crimean ports (Sevastopol, Kerci). In 2023, at the height of the Ukrainian attacks, huge queues formed at the ferry in Kerci, and residents were advised to avoid the harbour areas. Crimea’s internal logistical security – supplying the civilian population, industry – was threatened, forcing Russia to devote additional efforts (protecting the Crimean Bridge with barges, reconfiguring supply routes).

Russian naval losses have seriously eroded Moscow’s ability to fully secure its maritime economic interests in the Black Sea. Even if Russia does not face a blockade on its own exports (NATO has not imposed one, and Ukraine targets military, not civilian trade), Moscow’s frustration is obvious: it has been unable either to strangle Ukraine’s economy or fully protect its own flows. At the end of 2023, Russia resorted to bombing Ukrainian energy infrastructure and Danube harbours, but these actions cannot compensate for the loss of maritime control.