The Togliatti-Odesa ammonia pipeline A subject of negotiations?-Cam fl dr. Sorin Learschi –Maritime Security Forum

The US-Russia talks also touched on the very important topic of resuming Russian ammonia exports to Asia and Africa via a Ukrainian pipeline.

Discussions also included the negotiation of the initiative which currently allows the export of Ukrainian agricultural products from three Black Sea ports. But the talks aimed to remove some remaining “obstacles”.

One very important condition was Russia’s possibility of allowing Ukraine to resume exports of ammonia, a chemical used to make fertilizer. Earlier in the Russian-Ukrainian talks, the issue was discussed in the framework of negotiations on a broad prisoner exchange.

Along with Russia’s demand to use or even control Ukraine’s seaports on the Black Sea, there is also this major economic interest in using the ammonia pipeline between Togliatti (Russia) and Odessa (Ukraine), which has the capacity to load liquid ammonia, as well as process it for the production of chemical fertilizers for agriculture…

Background

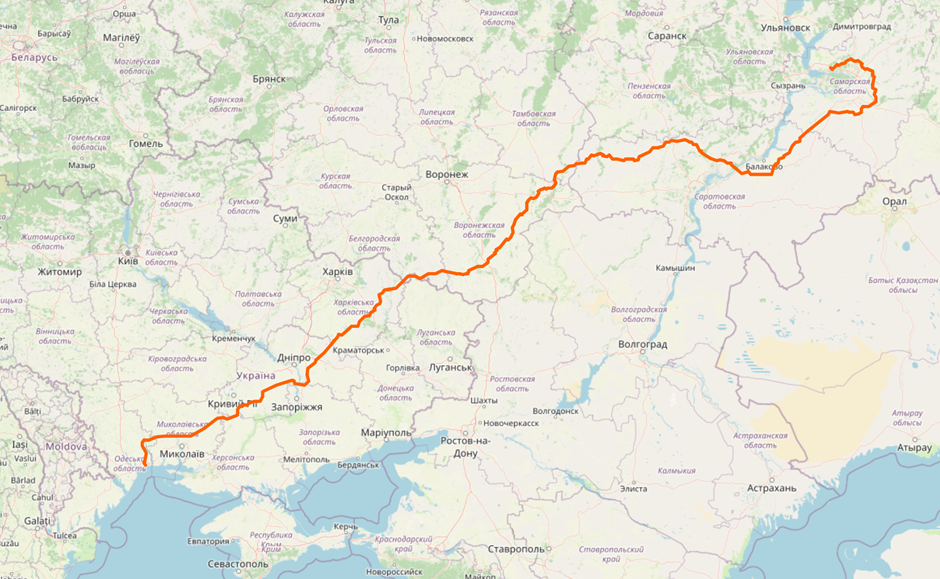

The Togliatti-Odesa ammonia pipeline was built between 1975 and 1981 and has a length of 2,471 km, of which 1,031 km cross Ukrainian territory. The pipeline connects Togliatti in Russia with the Ukrainian Black Sea port of Odessa. The pipeline was built as part of a joint project between TogliattiAzot, the world’s biggest ammonia producer, and Occidental Petroleum to facilitate ammonia exports to the global south. The Russian section of the ammonia pipeline is operated by OJSC Transammiak; the Ukrainian section is operated by State Enterprise Ukrkhimtransammiak.

In Odessa, the Odessa port plant specializing in ammonia operation) either pumps liquid ammonia onto ships for export or converts it into a range of products for export. This included 569,000 tons of ammonia-based fertilizers in 2014.

A branch of the pipeline is taken to the Stirol chemical plant in Horlivka, Donetsk region; however, ammonia transportation in this section of the pipeline was discontinued in 2014 for safety reasons.

Stirol, founded in 1933 in Horlivka, Donețk region, was one of the oldest and largest producers of nitrogen-based fertilizers in Ukraine: by 2014, it produced 1% of all nitrogen-based fertilizers globally. It was a subsidiary of Ostchem Holding, but after the occupation of eastern Donbas in 2014, the plant was left in an area claimed by the “Donetsk People’s Republic” and production ceased. Since then it has been inactive.

By 2018, the entire 200 km branch from Lozova to Stirol was emptied. TogliattiAzot looked for alternative options to the Togliatti-Odesa pipeline, such as ammonia transportation from the port of Taman, an option that was still being considered by the Russian authorities in 2024.

Emergency shut-off systems with valves were installed every 5.2 km. Ammonia remains liquid at pressures up to 35 atm and temperatures up to 4°C. To prevent corrosion, the transported ammonia contains 0.4% water. The 355 mm wide and 8 mm thick pipe is laid 1.4 m deep in the ground, and where the pipe passes through wet soil and over water bodies, 13 mm double-walled pipe with nitrogen-filled outer layer was used. The pipe was laid not less than 1 km from inhabited areas.

Since the beginning of the invasion in 2022, Stirol has been subject to sporadic damage due to fighting. The first recorded incident was on April 18, 2022, when an electrical transformer and warehouses with unknown contents were hit. In August 2022 there was an increase in facility targeting.

On August 12, 2022, at around 17:00 local time, images were posted on Telegram of a large column of black smoke rising from the area of the power plant following the bombing. Local groups reported that the burning building contained military equipment; pro-Russian media disputed this, saying that the fire was due to burning roofing material and that there was no threat of chemical pollution from the incident.

Two weeks later, there were two strikes, two days apart, on the same 110-kilowatt power station, with fires resulting from both incidents. Since December 2022, satellite imagery and social media posts have provided evidence of incidents of damage to the ammonia plant’s cooling unit, sulfur storage and mechanical repair shop. The canteens near the ammonium nitrate and urea workshops and the administrative buildings at the entrance to the plant were also damaged. The most recent incident was on August 24, 2023.

Damage assessment

The area around Stirol lies beyond the front line and has been occupied for some time. The fighting was less intense here than in other similar facilities in the “Donetsk People’s Republic”. Despite this, analysis of synthetic aperture radar damage mapping shows that at least 8% of the structures built on site have been damaged.

The pipeline and port facility in Odessa were shut down/conserved on February 24, 2022 due to the risks associated with the damage. The resumption of ammonia exports subsequently became a key Russian demand as part of the Black Sea Grain Initiative and was supported by the UN in response to food security concerns.

On June 5, 2023, shelling damaged the pipeline between the villages of Masyutivka and Zapadne in Kupiansk District, Kharkiv Region, resulting in the depressurization of the section.

The next day, military forces fired six times on the pipeline, again near the village of Masyutivka. Pro-Russian Telegram channels began circulating a video of a cloud of ammonia spreading from what appears to be a pumping station.

Other attacks were reported on the same section of the pipeline between June 10 and June 15, 2023.

The resolution of the available optical satellite imagery did not allow definitive observations of the damage to the pipeline, but suggests that ammonia gas was released between June 6 and June 13, 2023.

When depressurization of the pipeline occurred, an emergency shut-off valve was activated, limiting the leak to 134 tons. According to Ukrainian authorities, ammonia concentrations did not exceed dangerous concentrations in nearby settlements. The levels of ammonia in the air reached “up to 7 ng/m3, while the Ukrainian safety limit is up to 10 ng/m3”; however, the data provided by the authorities were inconsistent in places. Air sampling in the Slovyansk settlement, which was further away from the breach, confirmed that ammonia did not migrate.

Earlier modeling was undertaken for a Togliatti-Odesa pipeline depressurization event that involved an initial short-term high-pressure emission and residual leakage. This was undertaken at 35 atmospheres of pressure, but the actual pressure in the pipeline at the time of the bombing is unknown. The location of the incident means it was inaccessible for independent inspection, although the pipeline was designed with a number of safeguards.

Future risks to the ammonia pipeline will depend on whether it is reopened as part of an agreement between the warring parties.

In the aftermath of June 5, a Russian military blogger claimed that the event caused casualties among both Russian and Ukrainian fighters. This claim cannot be verified. Another account claimed that there were some civilian casualties but no military casualties. Russian-backed officials continued to spread news of ammonia leaks two weeks later without evidence.

Russia blamed Ukrainian sabotage groups for the incident, which occurred a month before the renewal of the Black Sea Grain Initiative.

Since the fall of 2022, UN-mediated negotiations have sought to include the ammonia pipeline in the Black Sea Grain Initiative, which would allow ammonia exports through the same Black Sea routes. Ukraine has been reluctant because a deal would allow Russia to reap profits of $2.4 billion a year, additional leverage in potential peace talks, and would carry the risk of a chemical accident. In May 2023, negotiations temporarily resumed with UN mediation for a short period.

MARITIME SECURITY FORUM